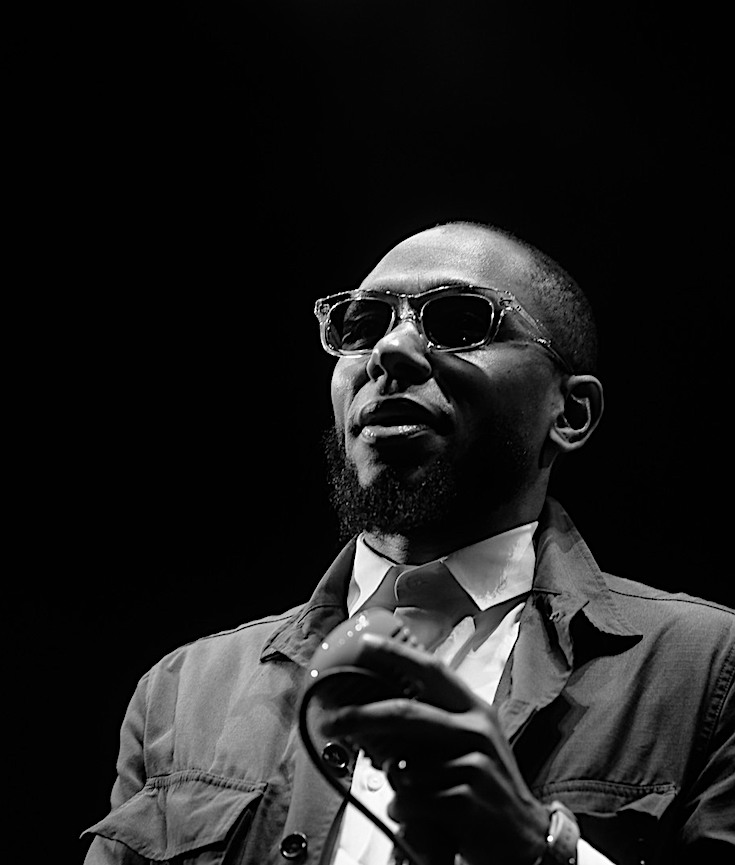

In the opening to her new book, Muslim Cool, the Purdue University professor Su’ad Abdul Khabeer makes an ambitious declaration of intent: Her research “poses a direct challenge to [the] racialization of Muslims as foreign and as perpetual threats to the United States.” For more than a decade, Khabeer has worked with young Muslims, largely in America, who are interested in art, fashion, and activism—and think about all of these things through the lens of hip hop. While she studied people from a variety of ethnic and national backgrounds, she focuses on the intersections between hip-hop culture, black culture, and Islam, arguing that all of these cultures define what is “cool” in the United States.

Khabeer is a Muslim who defines herself as a “hip-hop head.” She’s arguably a product of “Muslim cool”: “Hip hop is the soundtrack to my life,” she writes. “Growing up in Brooklyn and particularly being a teenager during the golden era of hip hop made my connection with it even more meaningful. I was black and Muslim … and the music and culture of hip hop were replete with Islamic references and pro-black and pan-African messages.”

[mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

While Muslim Cool celebrates the spiritual grounding of hip hop and tries to tease apart its complex relationships with race and religion, the context surrounding the book is perhaps what’s most challenging about it. During this election cycle, rhetoric about Islam has been disturbing and violent. Last year, hate crimes against Muslims increased, and at various points, Donald Trump has proposed religion-based bans on all Muslims seeking to enter the United States. The idea that Muslims create “cool” in American culture while also being severely marginalized is dizzying.

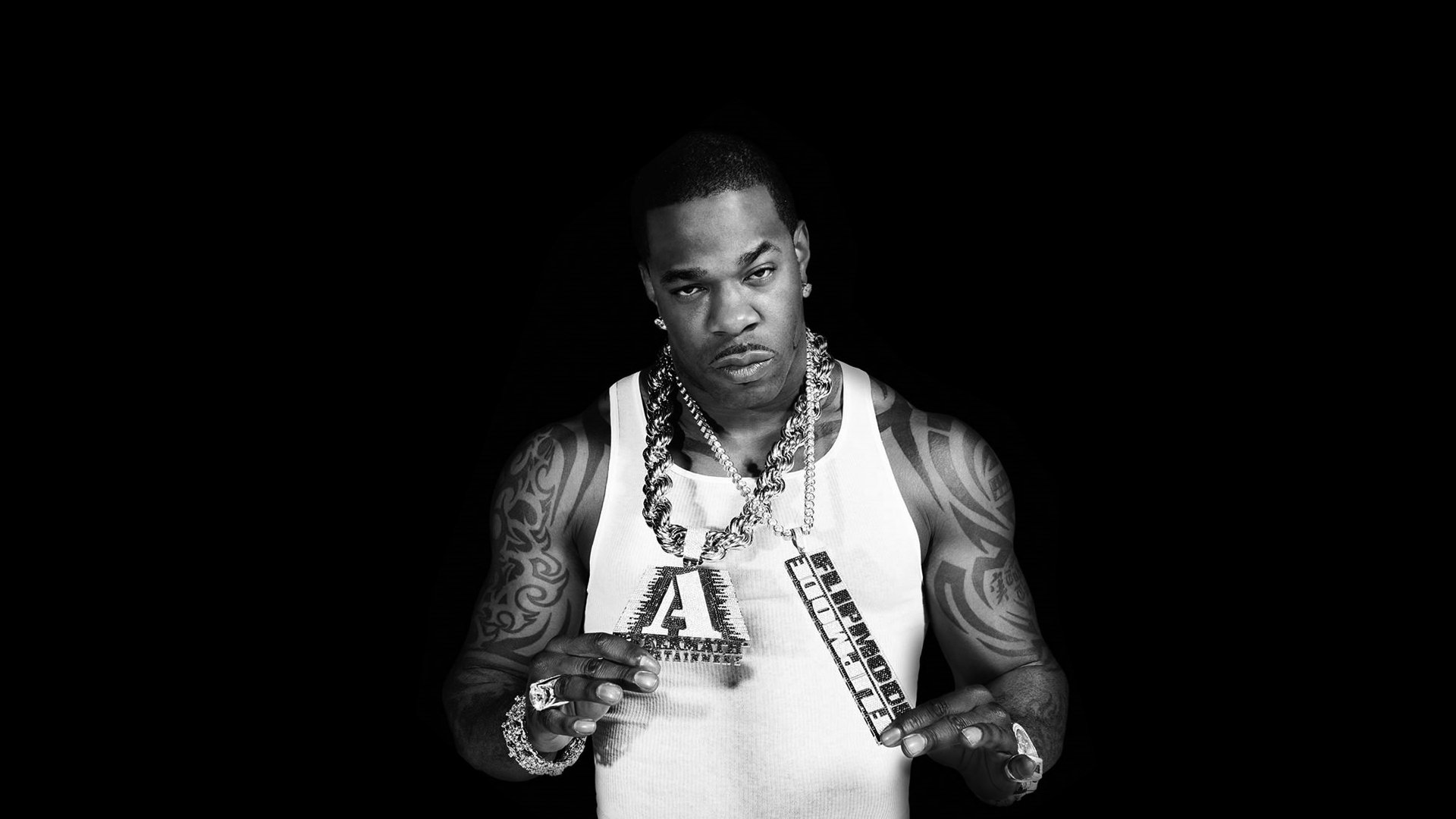

Hip hop music, also called hip-hop or rap music, is a music genre formed in the United States in the 1970s that consists of a stylized rhythmic music that commonly accompanies rapping, a rhythmic and rhyming speech that is chanted. It developed as part of hip hop culture, a subculture defined by four key stylistic elements: MCing/rapping, DJing/scratching, break dancing, and graffiti writing. Other elements include sampling (or synthesis), and beatboxing.

While often used to refer to rapping, “hip hop” more properly denotes the practice of the entire subculture. The term hip hop music is sometimes used synonymously with the term rap music, though rapping is not a required component of hip hop music; the genre may also incorporate other elements of hip hop culture, including DJing, turntablism, and scratching, beatboxing, and instrumental tracks.

Hip hop as music and culture formed during the 1970s when block parties became increasingly popular in New York City, particularly among African-American youth residing in the Bronx. At block parties DJs played percussive breaks of popular songs using two turntables to extend the breaks.[clarification needed] Hip hop’s early evolution occurred as sampling technology and drum-machines became widely available and affordable. Turntablist techniques developed along with the breaks and the Jamaican toasting vocal style was used. Rapping developed as a vocal style in which the artist speaks along with an instrumental or synthesized beat. Notable artists at this time include DJ Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five, Fab Five Freddy, Marley Marl, Afrika Bambaataa, Kool Moe Dee, Kurtis Blow, Doug E. Fresh, Whodini, Warp 9, The Fat Boys, and Spoonie Gee. The Sugarhill Gang’s 1979 song “Rapper’s Delight” is widely regarded to be the first hip hop record to gain widespread popularity in the mainstream. The 1980s marked the diversification of hip hop as the genre developed more complex styles.[16] Prior to the 1980s, hip hop music was largely confined within the United States. However, during the 1980s, it began its spread and became a part of the music scene in dozens of countries. (Wikipedia).

You must be logged in to post a comment.