[dropcap]In[/dropcap] the natural course of events, humans fall sick and die. Patients hope for miraculous remedies to restore their health.

We all want our medicines to work for us in wondrous ways. But how are human subjects chosen for experiments? Who bears the burden of risk? What ethical brakes keep scientific enthusiasm from overwhelming vulnerable populations? Who goes first?

Today, the question of underrepresented minorities in medical experimentation is still volatile. Minorities, especially African-Americans in the U.S., tend to be simultaneously underrepresented in medical research and historically exploited in experimentation.

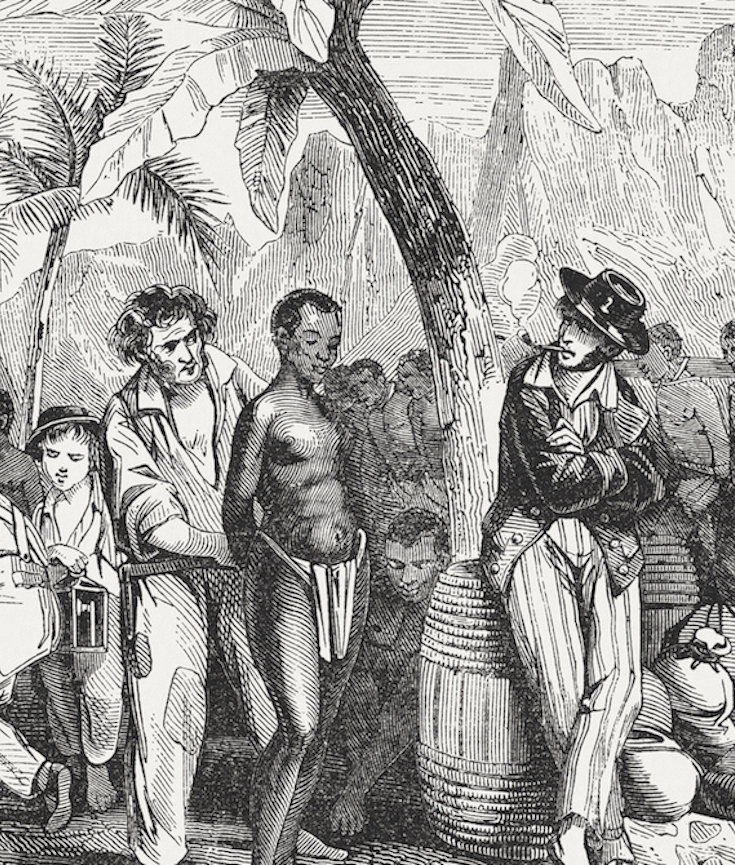

My new book, “Secret Cures of Slaves: People, Plants, and Medicine in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic,” zeroes in on human experimentation on Caribbean slave plantations in the late 1700s. Were slaves on New World sugar plantations used as human guinea pigs in the same way African-Americans were in the American South centuries later?

[mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

TUSKEGEE SYPHILIS EXPERIMENT | 1932-72

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, also known as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study or Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment was an infamous clinical study conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the U.S. Public Health Service. The purpose of this study was to observe the natural progression of untreated syphilis in rural African-American men in Alabama under the guise of receiving free health care from the United States government.

The Public Health Service started working on this study in 1932, in collaboration with Tuskegee University, a historically black college in Alabama. Investigators enrolled in the study a total of 600 impoverished, African American sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama. Of these men, 399 had previously contracted syphilis before the study began, and 201 did not have the disease. The men were given free medical care, meals, and free burial insurance for participating in the study. After funding for treatment was lost, the study was continued without informing the men they would never be treated. None of the men infected were ever told they had the disease, and none were treated with penicillin even after the antibiotic was proven to successfully treat syphilis. According to the Centers for Disease Control, the men were told they were being treated for “bad blood”, a local term for various illnesses that include syphilis, anemia, and fatigue.

The 40-year study was controversial for reasons related to ethical standards. Researchers knowingly failed to treat patients appropriately after the 1940s validation of penicillin was found as an effective cure for the disease they were studying. Revelation in 1972 of study failures by a whistleblower led to major changes in U.S. law and regulation on the protection of participants in clinical studies. Now studies require informed consent, communication of diagnosis, and accurate reporting of test results. (Wikipedia).

You must be logged in to post a comment.