[dropcap]Chester[/dropcap] B. Himes was born in 1909 into an educated, prospering black family living in Jefferson City, Mo., across Lafayette Street from the Lincoln Institute, the African American college where his parents taught. This places him in that generation of black Midwesterners including Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas and Josephine Baker — artists who would bring so much talent and creativity to Harlem, Paris and the New Negro Renaissance of the 1920s. But Himes’s early years did not follow that path.

As his family fell apart, Himes became derelict, delinquent and “out of control.” In 1928, he was arrested for breaking into the home of a wealthy Cleveland couple and robbing them. Himes pleaded guilty, seeking leniency. No doubt because he already had a record, the judge sentenced 19-year-old Himes to 20 years in prison. He entered the state prison in Columbus, where Ohio State University is also located — and where Himes had briefly been a student.

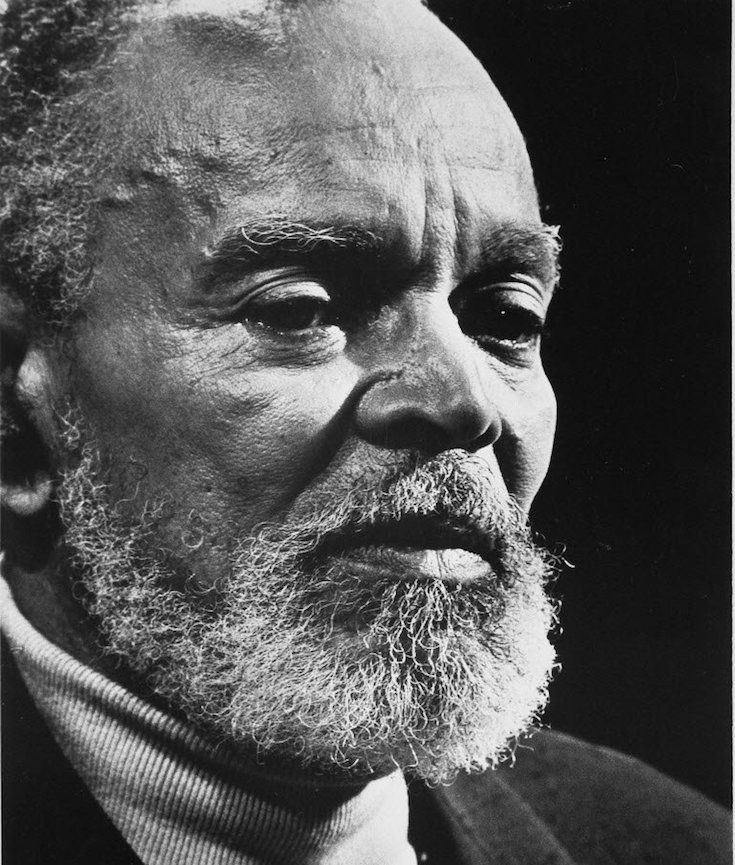

In his vivid, engrossing biography, Lawrence Jackson, a professor at Johns Hopkins, gives us an in-depth portrait of Himes, an African American writer whose 20 published books stirred controversy with their depictions of sexuality, racism and social injustice. The writings were often more sensational than revered — and raised questions as to Himes’s place in modern literary history. Jackson takes on those questions in a biography that is a revisionist literary history accommodating and embracing a black author who wrote about black detectives, white women, labor struggles, Harlem streets — and did so while living outrageously both here and abroad.

[mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES | HBCU

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African American community. They have always allowed admission to students of all races. Most were created in the aftermath of the American Civil War and are in the former slave states, although a few notable exceptions exist.

There are 107 HBCUs in the United States, including public and private institutions, community and four-year institutions, medical and law schools.

Most HBCUs were established after the American Civil War, often with the assistance of northern United States religious missionary organizations. However, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania (1837) and Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) (1854), were established for blacks before the American Civil War. In 1856 the AME Church of Ohio collaborated with the Methodist Episcopal Church, a predominantly white denomination, in sponsoring the third college Wilberforce University in Ohio. Established in 1865, Shaw University was the first HBCU in the South to be established after the American Civil War.

The Higher Education Act of 1965, as amended, defines a “part B institution” as: “…any historically black college or university that was established before 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans, and that is accredited by a nationally recognized accrediting agency or association determined by the Secretary [of Education] to be a reliable authority as to the quality of training offered or is, according to such an agency or association, making reasonable progress toward accreditation.”Part B of the 1965 Act provides for direct federal aid to Part B institutions. (Wikipedia).

You must be logged in to post a comment.