[dropcap]The[/dropcap] road to Virginia Episcopal School was more secluded in those days, winding a few miles from the white section of segregated Lynchburg through a wood of maple and oak to the school’s rolling campus, shielded by trees and the more distant Blue Ridge Mountains. The usual stream of cars navigated the bends on the first day of school, white families ferrying their adolescent sons. Like nearly every other elite prep school in the South, it had been the boarding school’s tradition since its founding in 1916 that its teachers guide white boys toward its ideal of manhood — erudite, religious, resilient. But that afternoon of Sept. 8, 1967, a taxi pulled up the long driveway carrying a black teenager, Marvin Barnard. He had journeyed across the state, 120 miles by bus, from the black side of Richmond, unaccompanied, toting a single suitcase. In all of Virginia, a state whose lawmakers had responded to the 1954 court-ordered desegregation of public schools with a strategy of declared “massive resistance,” no black child had ever enrolled in a private boarding school. When Marvin stepped foot on V.E.S. ground, wearing a lightweight sport jacket, a white dress shirt, a modest necktie and a cap like the ones the Beatles were wearing, the white idyll was over.

Marvin had just turned 14 when he arrived, and at a little over five feet tall and 100 pounds, he was a tiny thing. His face was boyishly open, eyes and mouth big and bright, black hair that grew in waves toward a lopsided widow’s peak. His skin was yellow-brown. Marvin had the spirit of a bouncing ball, and back home in Richmond he’d kept his classmates and teachers laughing. In all his years of schooling, he’d never earned a grade other than A. The old couple who raised him, his aunt and uncle, had given him a dime for each perfect report, but money wasn’t Marvin’s motivation. He lived to please them, and after his aunt died when he was 12, Marvin lived to please his uncle. Going off to V.E.S. had delighted him and just about everyone else. “The neighbors and the other kids, they were just excited,” Marvin recalled. “The thing that gave me such a rush was that I could see it in their eyes. It’s like: ‘Well, you go, and you show them. You show them what you can do. You show them for us.’ ”

[mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

Virginia Episcopal School | Photo Credit

Virginia Episcopal School | Photo Credit

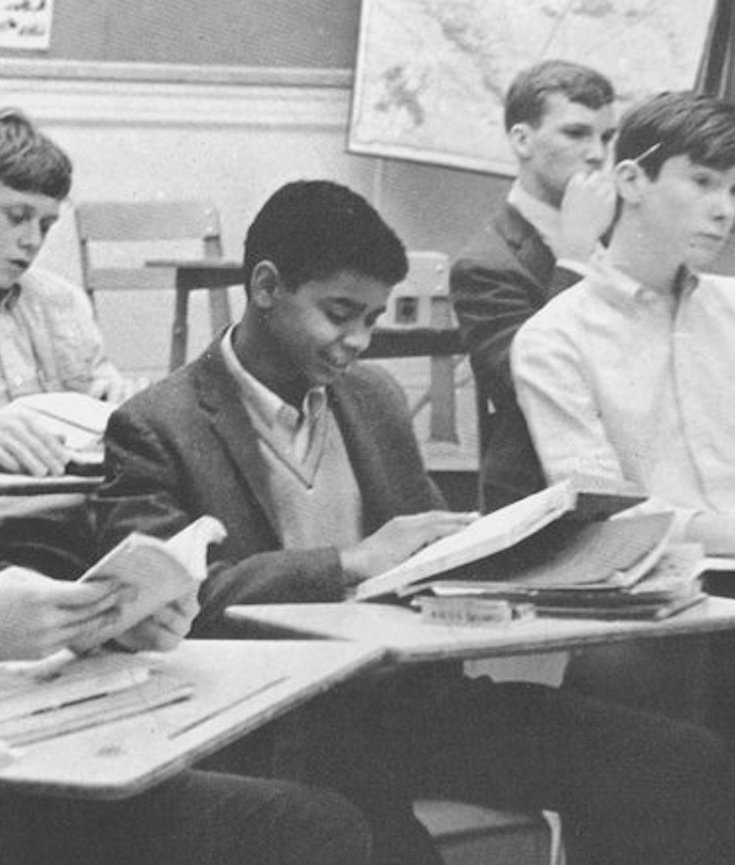

Virginia Episcopal School | Photo Credit

Virginia Episcopal School | Photo Credit

Virginia Episcopal School | Photo Credit

Virginia Episcopal School | Photo Credit

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY & CULTURE | WASHINGTON, DC

The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture. It was established by Act of Congress in 2003, following decades of efforts to promote and highlight the contributions of African Americans. To date, the Museum has collected more than 36,000 artifacts and nearly 100,000 individuals have become charter members. The Museum opened to the public on September 24, 2016, as the 19th and newest museum of the Smithsonian Institution. (Biography.com).

You must be logged in to post a comment.