[dropcap]Cyntoia[/dropcap]he had even made his first movie, Spike Lee used to fantasize about three things: season tickets at the Garden, a brownstone in Fort Greene like the one that he was raised in and a house in the historically black Oak Bluffs section of Martha’s Vineyard. In 1986, after writing, producing, directing and acting in his infectious debut, “She’s Gotta Have It,” a stylish, edgy rom-com about a libidinous young woman juggling three lovers, those Knicks seats came first. The two homes swiftly followed, and within a decade, Lee’s status and celebrity had catapulted him, practically against his will, from Da Republic of Brooklyn, as he likes to call it in emails, into a 8,200-square-foot Upper East Side townhouse that was previously home to Jasper Johns. But the getaway in Massachusetts, situated next to the 18th hole at the Farm Neck Golf Club, has never required upgrading.

As I was preparing to visit him there this summer, Lee warned me that the second week of August is when “everybody” descends on the Vineyard. He did not lie. The annual African-American Film Festival was happening, and the sheer saturation of black achievement on display — on an 87-square-mile strip of land that is home to some of the first integrated beaches in the country and also synonymous with the liliest-lily-white establishment — was something to behold. In the previous 24 hours, both Barack Obama and the two-time N.B.A. champion Ray Allen had teed off behind Lee’s house; as my Uber turned down Lee’s dirt driveway, Henry Louis Gates Jr. pedaled past on a tricycle. Lee has long been a fixture at the festival, and this year he would be previewing his latest project, a 10-episode Netflix reboot of the very film that made him a star: “She’s Gotta Have It.” A late-career foray into prestige television, the series, released this week, marks a homecoming of sorts, as well as a risky departure. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

My driver, an amiable 6-foot-8 Jamaican man who grew up in Canarsie, became star-struck when Lee came to meet our car and did not want to pull away. “What high school you go to?” Lee asked him by way of greeting. Schools and sports teams are the kinds of affiliations that genuinely mean a lot to him. The driver’s answer seemed satisfactory, but then Lee noticed his backward baseball cap and asked to see the front of it. The driver sheepishly swiveled it around. “It’s a B for Brooklyn,” he tried.

“That ain’t no Brooklyn! That B is for Boston!” Lee erupted, only half-jokingly. “Do you see the flag?” He pointed to an enormous navy-blue-and-white New York Yankees standard hoisted high above his property, so large it flapped in slow motion, as if underwater. “Look at the flag!”

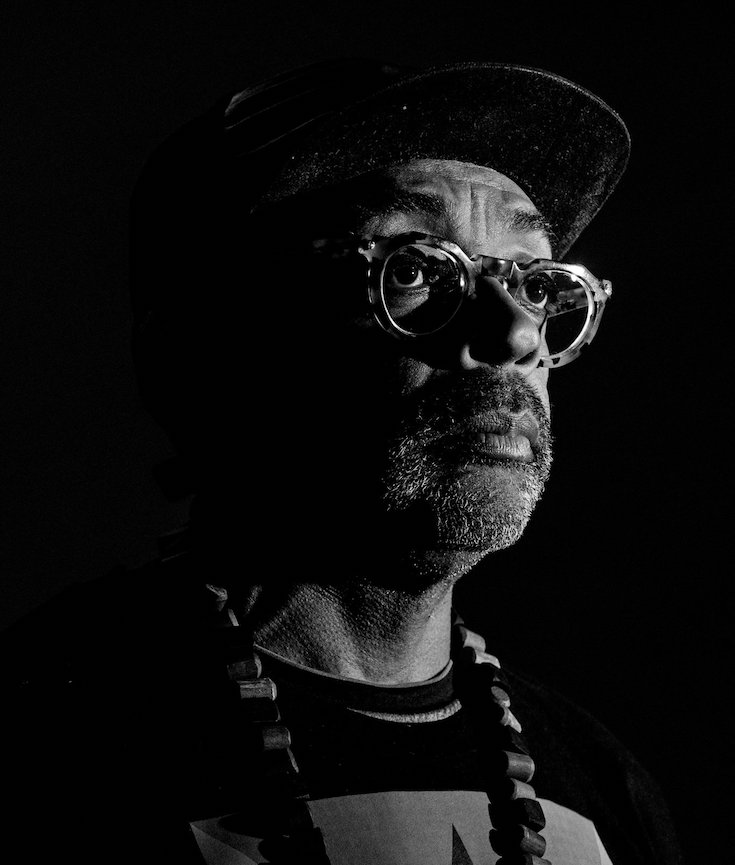

Mamadi Doumbouya for The New York Times | Photo Credit

Mamadi Doumbouya for The New York Times | Photo Credit

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY & CULTURE | WASHINGTON, DC

The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture. It was established by Act of Congress in 2003, following decades of efforts to promote and highlight the contributions of African Americans. To date, the Museum has collected more than 36,000 artifacts and nearly 100,000 individuals have become charter members. The Museum opened to the public on September 24, 2016, as the 19th and newest museum of the Smithsonian Institution. (Website).

You must be logged in to post a comment.