[dropcap]Metaphors[/dropcap] sustain us. I have always clung to the story in Plato’s Symposium of two halves meeting after a long separation in “an amazement of love and friendship and intimacy,” because the pursuit of this dream drives so many of us—or, at least, those of us who long to be irrevocably transformed by closeness. It lies at the core of the events that prompted the journey I’m taking now, which finds me sitting in a cold carriage on a fast train headed toward Haverfordwest, a small market town in southwest Wales. I am travelling into blackness, or, more specifically, blackness as a trope, blackness as it was defined and revised, espoused and abandoned, by two colored girls known as “the silent twins”—the identical twins June and Jennifer Gibbons, who, living in Great Britain with virtually no education and no peers, developed brutal skills of self-invention and cleaved to their own ferocious intimacy, their continually “amazed” relationship with their other half. For most of their lives together, they refused to speak to anyone but each other—a refusal that led to their emotional exile, their institutionalization, and, eventually, to the misguided appropriation of their story by activists and theorists who used it to pose questions about the nature of identity and the strange birthright that twins are forced to bear.

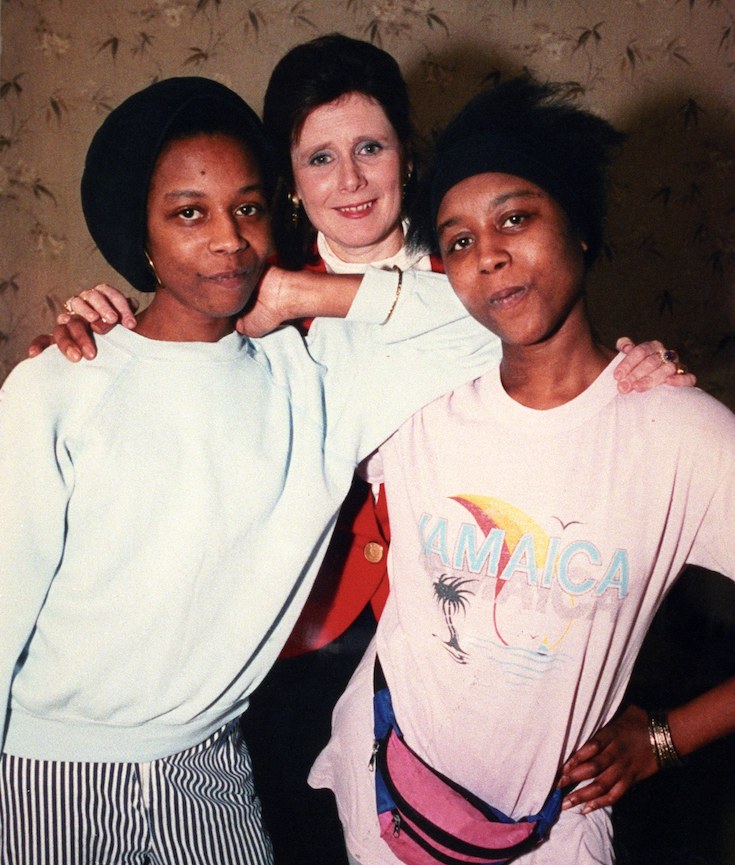

It is a cold, gray day, the kind of day that Americans, reading English novels, imagine being far more picturesque than the reality. The long train hugs the coast, close enough for me to see the gray-green water rolling and lapping—almost close enough for me to reach out and touch it. As the train approaches the Haverfordwest station, I see June Gibbons, the only black person on the platform. She spots me, too, the only black person on the train, and she nods as I disembark. She is wearing jeans and a white T-shirt and black boots and a large blue jacket, in which her thin frame seems to swim. She is accompanied by a pleasant white woman who works in the halfway house where June is living. June’s face—the face I have already studied in photographs—is long and narrow and fine. She smiles when I introduce myself, exposing sharp teeth stained by tobacco. Almost at once, she tells me, in a muffled, fast voice, that we should hurry into a taxi. Actually, it’s more of a command: “Get in the taxi!” I sit in the front seat, next to the driver. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

“June would like you to come and have tea,” her companion says, with a bright smile.

We drive through the town: steep hills, shops, children in school uniforms shouting and jostling one another, housing estates where all the houses look the same—two-storied brown stucco with green or white or red doors and neat little paths and patches of wet green separating them from each other. The metal-gray sky hangs low, as smoke drifts from the brick chimneys. June asks about the title of the book I am carrying, “In Search of Wales,” by H. V. Morton. “Well, he’s found it, then!” she says quickly, to no one in particular. She laughs, but examines me with the eyes of someone who, while waiting to be seen, has learned how to watch closely.

June Alison and Jennifer Lorraine Gibbons were born at an R.A.F. hospital in Aden, in the Middle East, on April 11, 1963. June arrived first, at 8:10 a.m., but Jennifer, born ten minutes later, seemed to be the stronger twin, more alert and physically robust. Their parents were from Barbados: Aubrey, tall, handsome, and stiff, and Gloria, whose soft eyes gave her a gentle, yielding appearance. She relied on Aubrey to make decisions for her, just as June would later defer to Jennifer. In 1960, Aubrey, an Anglophile who had long dreamed of being a proper English gentleman, had decided this: he would make a life for himself and his family (a daughter, Greta, had been born in 1957; a son, David, in 1959) away from his homeland. He went to stay with a relative in Coventry and soon qualified as a staff technician for the R.A.F. Gloria followed, with Greta and David, several months later.

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY & CULTURE | WASHINGTON, DC

The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture. It was established by Act of Congress in 2003, following decades of efforts to promote and highlight the contributions of African Americans. To date, the Museum has collected more than 36,000 artifacts and nearly 100,000 individuals have become charter members. The Museum opened to the public on September 24, 2016, as the 19th and newest museum of the Smithsonian Institution. (Website).

You must be logged in to post a comment.