[dropcap]This[/dropcap] widely accepted narrative of protests by white “anti-busers” against court-ordered integration portrays school integration as a failure and an aberration in the liberal “city on a hill.” In the rare instance that African Americans make an appearance, they are portrayed as apathetic bystanders or victims. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

While the fight for integration in the South is depicted as a morally just battle led by African American freedom fighters, most accounts of the quest for school desegregation in the North portray these efforts as disruptive and misguided. The “Boston busing” story plays a central role in reinforcing a powerful myth of southern exceptionalism that portray northern segregation as more racially benign and less institutionalized than its Southern counterpart.1 It distorts our understanding of the civil rights movement by obscuring the foundational role of racial inequality in our nation’s history.

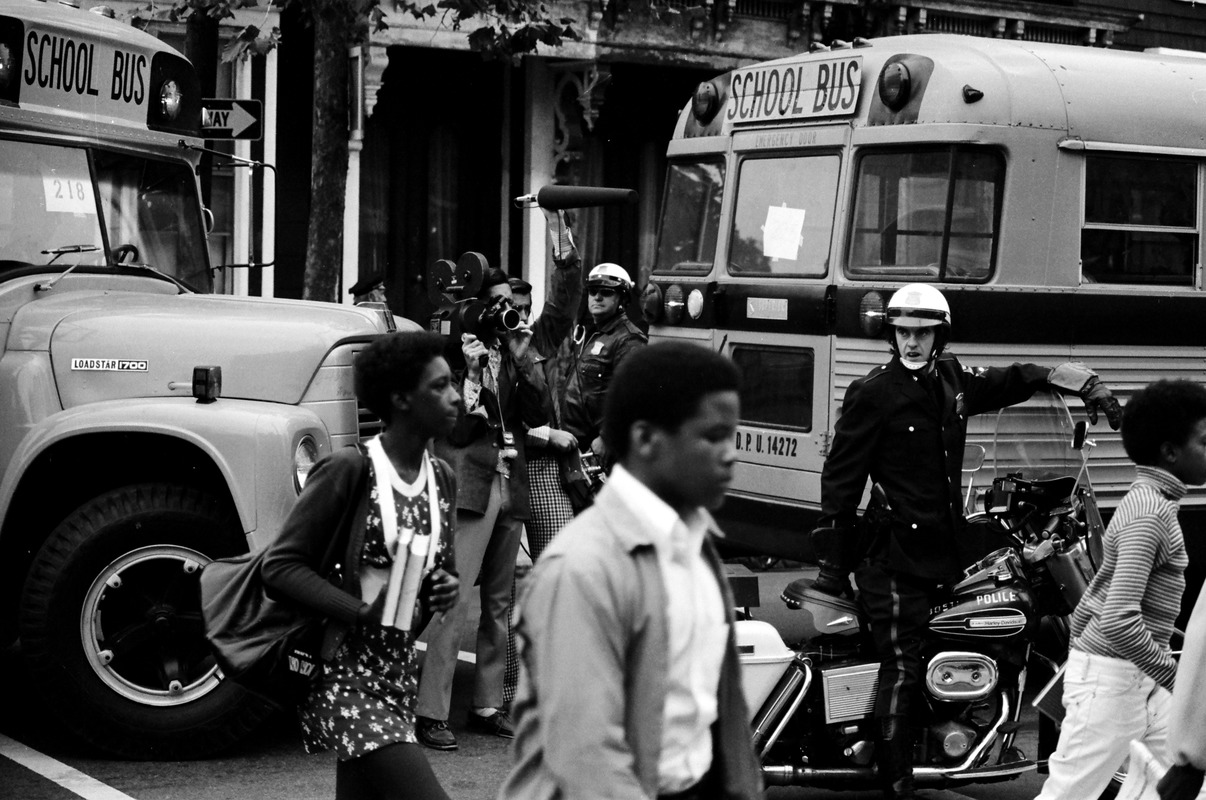

AP Photo/Peter Bregg | Image Credit

AP Photo/Peter Bregg | Image Credit

The history of Black civil rights activism in Boston shows that the South did not have a monopoly on either white supremacy or Black activism. From the mid-1940s through the 1970s Black Bostonians waged a fierce battle for racial justice in a deeply segregated and racially hostile city. They pushed for improvements in the quality of education, to end segregation, and for power for the people in school governance. Activists employed every strategy imaginable. They staged sit-ins and demonstrations, successfully lobbied for the passage of legislation, created freedom schools, and ran their own desegregation programs. After decades of activism, Black Bostonians turned to the courts as a last resort, filing suit in the case of Morgan v. Hennigan. In 1974 the courts ruled in the plaintiffs’ favor, ordering the desegregation of the Boston Public Schools.

You must be logged in to post a comment.