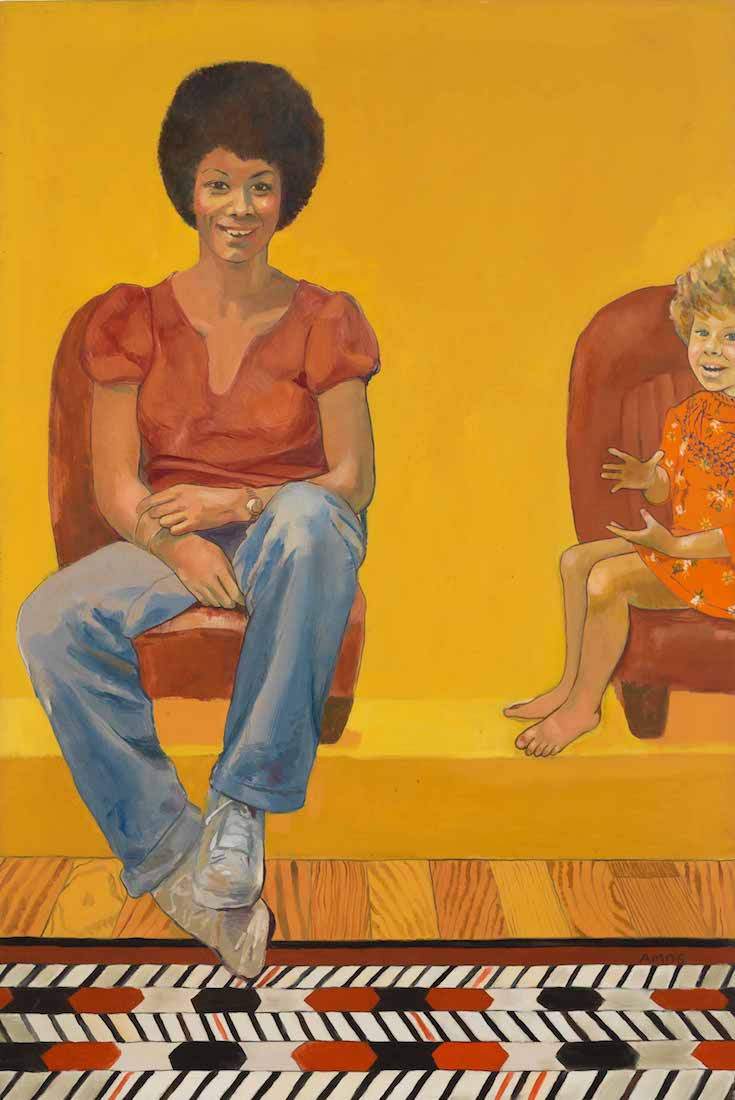

Emma Amos, Eva the Babysitter (1973), Featured Image Credit

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] few years ago, when I was a Fulbright Scholar in Britain, students gushed to me about their all-time favorite period in United States history: the heroic civil rights and Black Power era of the 1960s and 1970s. That’s when America was really fascinating, they told me, when issues were clear, and the right Americans made their voices heard. Many Americans feel this way, too. It is true that the civil rights revolution enkindled the concept of black power, which galvanized black artists—playwrights, choreographers, filmmakers, musicians, as well as visual artists—to make work that reflected the ideologies and energies of the era. It really did seem in the 1960s and 1970s that artists could make a difference in the struggle against racial discrimination by joining political activists as a force against white supremacy. Those young people in the UK were right to imagine a time when valiant Americans were outspoken and relatively united. And here I stress “imagine,” because in fact, ideological disagreements had hardly disappeared at that time. Last year, an ambitious art exhibition captured these hopes in visual form.

I come to “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” with two identities: as a historian and as a visual artist. I am interested in art history: in the machinations of history and memory as they apply to art, and in changes in taste and how they relate to power, money, and cultural visibility. As an artist, I’m attentive to how art is presented and actually looks in physical space. This piece, the first of a two-part review, focuses on the catalogue and how the works and ideas of the exhibition are represented in a book, an object that I hold in my hand in Newark, New Jersey (and an object of great beauty it is—a museum artifact in its own right). In a second piece, I will review the “Soul of a Nation” show at the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual: Baptism, 1964, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian/Artbook, D.A.P.

Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual: Baptism, 1964, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian/Artbook, D.A.P.

You must be logged in to post a comment.