[dropcap]Robert[/dropcap] Adler was a thirtysomething attorney at a small Washington firm in the late 1970s when a woman arrived in his office to discuss her problems at work. The woman, Sandra Bundy, was an employment specialist at DC’s Department of Corrections, where she helped former inmates find jobs after their release. About four years earlier, she explained, her superiors had begun making repeated—and unwanted—sexual advances toward her. After she rebuffed them, things got worse. When she complained to a more senior manager about the treatment, he said he couldn’t blame a man for wanting to take her to bed. “Let’s talk about you and me,” he later said. “When are we going to get together?” Appalled, she reached out to the director—a man who had also propositioned her in the past. He was of little use. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

[jg-ffw] [/jg-ffw]

[/jg-ffw]

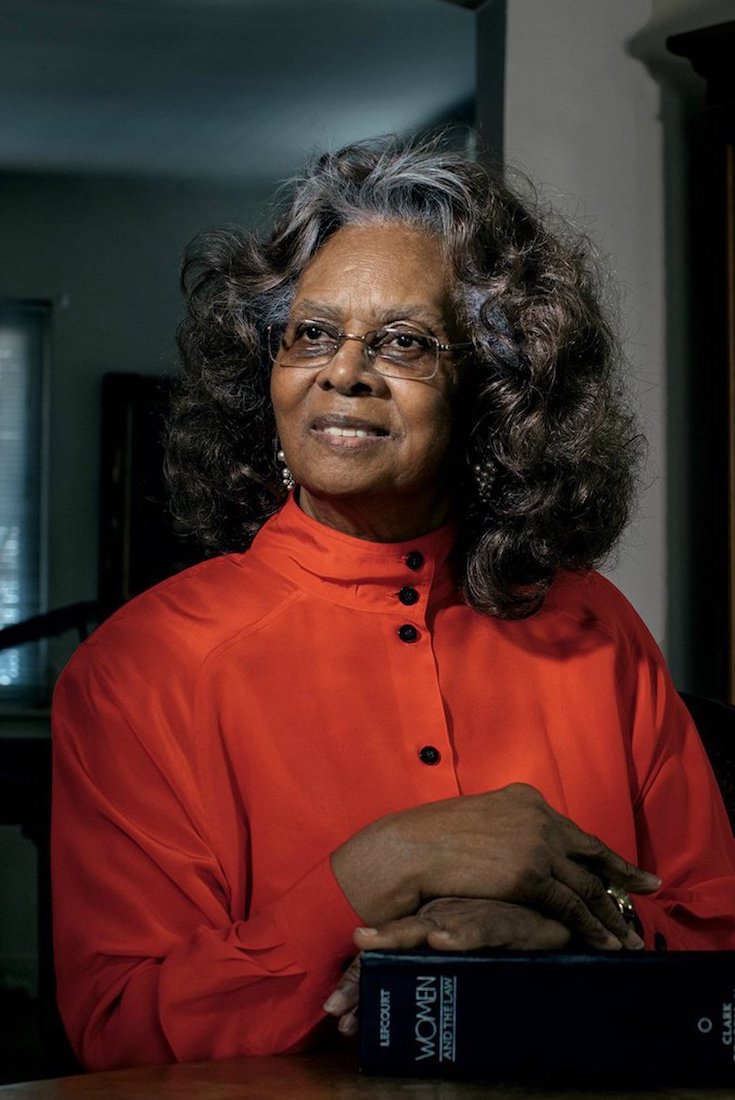

Bundy, a single mother, had joined the city government because it offered opportunities for advancement that she needed to support her children. She was, Adler recalls, a “smart, elegant, tough lady.” But the harassment had left her badly damaged. Could the young lawyer help?

Adler was an odd choice for the assignment. In the few years since launching his firm, he’d handled personal-injury cases, breach of contract, and divorce—never anything like this. Worse, Bundy’s claims fell into a legal gray area. She hadn’t been sexually assaulted or been denied employment because of her gender. Instead, she’d experienced a form of abuse not yet written into American law. Taking her case would be a tedious, expensive, and uncertain endeavor, requiring Adler’s team to argue new legal theories—with little financial upside.

[jg-ffw] [/jg-ffw]

[/jg-ffw]

As Adler listened to her story, however, he felt compelled to act. In 1977, Bundy sued the director of the Corrections Department in federal court. “I had no optimism that we were going to win this thing, because we were really in uncharted waters,” Adler says. “But I didn’t care.”

Today, some 40 years after she first walked into Adler’s office, Bundy’s lawsuit is considered a seminal event in the establishment of sexual harassment as a legal concept in America. “What is so incredibly significant about the case was finding that sexual harassment itself—the doing of it—was sex discrimination,” says Catharine MacKinnon, a University of Michigan law professor and a leading scholar on the issue. “That has been world-changing.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.