[dropcap]HERE[/dropcap] is an oversized desk calendar, used by many of his fellow employees, detailing transactions that are now described as fraudulent. And there is a taped telephone call in which a boss proposed to ”window dress” the company’s balance sheet. And there is an auditors’ report that raised no alarm.

In a case that has produced a mountain of evidence, these are only fragments. Still, they are enough to give hope to Joseph Jett, a pariah on Wall Street.

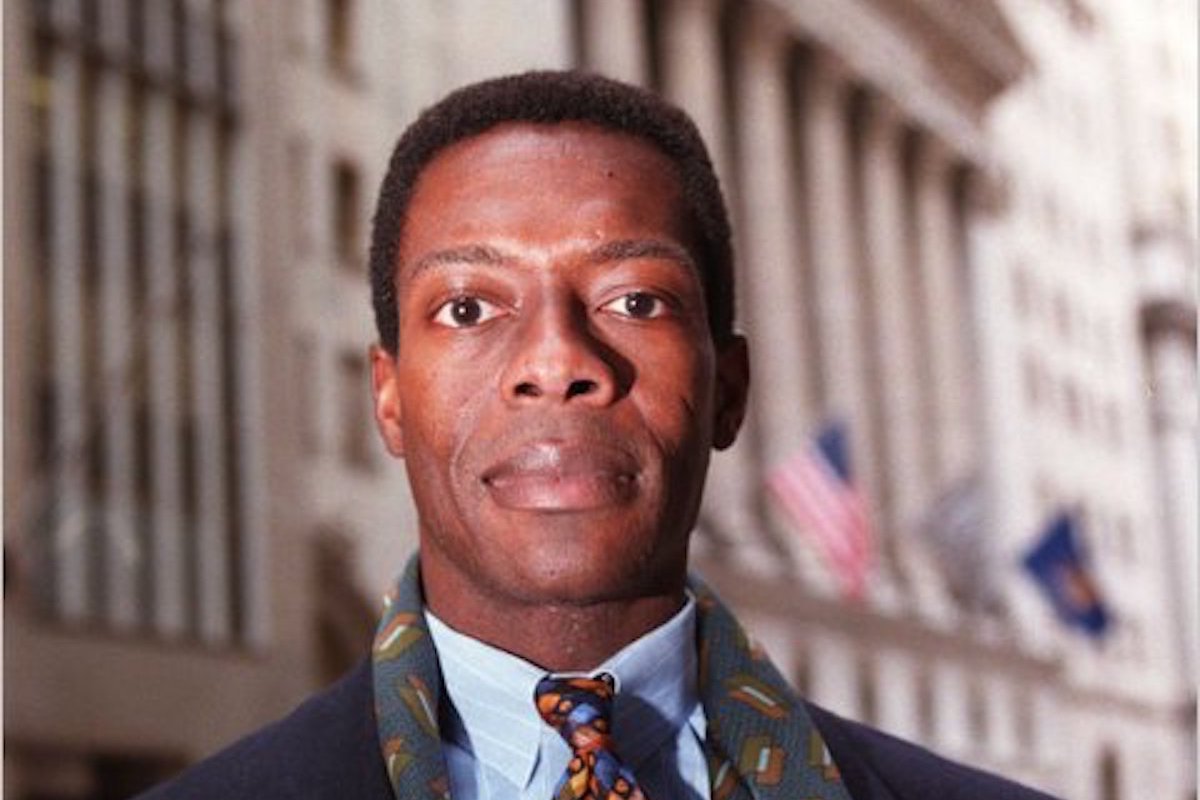

Month after month, the former superstar bond trader at Kidder, Peabody & Company has tediously sorted through 429 boxes of documents, computer records and tapes, trying to refute accusations that he engineered an astounding $339 million in phony profits. Between odd jobs on construction sites and making deliveries — and occasionally investing on others’ behalf — Mr. Jett has acted as his own paralegal, rummaging for anything that might clear his name.

Now Mr. Jett’s melancholy but tenacious three-year struggle is nearing an end. With an administrative law judge’s ruling expected in the next few months, Mr. Jett will be certified as either one of Wall Street’s great scoundrels or one of its most vilified scapegoats.

As he awaits the ruling — on a Securities and Exchange Commission complaint against him — Mr. Jett and his lawyers offer up the scribblings of his former colleagues as confirmation that Kidder officials knew all about his trading strategies. And in some finger-pointing of their own, he and his lawyers cite cryptic recorded conversations as evidence that top officials urged him to help deceive General Electric, Kidder’s parent at the time. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

Considering the intensity of his public shaming when he was dismissed in April 1994, Mr. Jett has been able to mount a remarkably vigorous defense. Just before Christmas, a securities arbitration panel awarded him $1 million of his Kidder bonuses after ruling that the firm was unable to prove he engaged in ”fraud, breach of duty and unjust enrichment.”

The arbitration hearing and a trial last summer on the S.E.C. accusations have produced a mass of intriguing documents and sworn testimony, while subsequent interviews have filled in some gaps. At the least, the evidence adds up to an extraordinary chronicle of negligence by Kidder officials who were supposed to supervise Mr. Jett but missed one opportunity after another to halt his trading. Instead, they happily allowed his trading and generously rewarded it. Dozens of people were aware of a central component of his strategy, but no one, either out of ignorance or worse, objected to it as being based on an outright fiction.

Some former colleagues of Mr. Jett suspect that the firm turned a blind eye because of an eagerness to breed star traders, and to impress G.E., which in 1994 finally sold the firm out of disgust.

After an internal investigation, a humiliated Kidder and G.E. acknowledged intolerable lapses of supervision. But whether Kidder officials countenanced Mr. Jett’s activities, explicitly or tacitly, remains an issue — one that may only be settled when a judge decides whether to fine him $20 million and expel him for life from the securities industry, as the S.E.C. has requested.