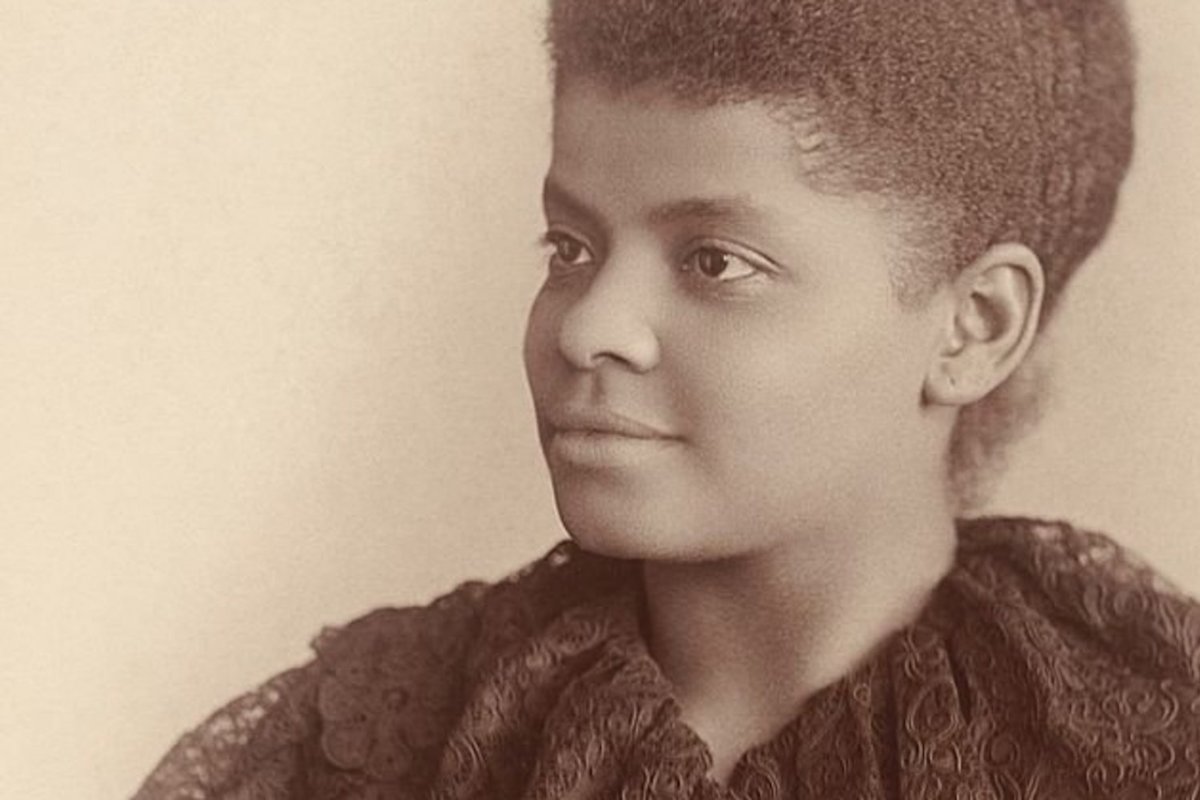

[dropcap]One[/dropcap] day in September of 1883, a 20-year old Ida B. Wells sat in the rear car of the train, minding her business, reading the newspaper. She was traveling from Memphis to Woodstock, Tennessee where she taught public school and was on the path to becoming a world-renowned anti-lynching activist and journalist. When the white conductor came to collect her ticket, he told her she needed to move to the front car because the rear was for whites only. “I replied that I would not ride in the forward car, that I had a seat and intended to keep it,” she later wrote in her lawsuit against the Chesapeake, Ohio and Southwestern Railroad. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

The conductor told Wells he’d treat her like a lady, but staying in the rear car was not an option. She retorted that if he wanted to treat her like a lady he’d leave her alone.

“I refused, saying that the forward car [closest to the locomotive] was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies’ car, I proposed to stay. . . [The conductor] tried to drag me out of the seat, but the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand,” she wrote in her autobiography. “I had braced my feet against the seat in front and was holding to the back, and as he had already been badly bitten he didn’t try it again by himself. He went forward and got the baggageman and another man to help him and of course they succeeded in dragging me out.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.