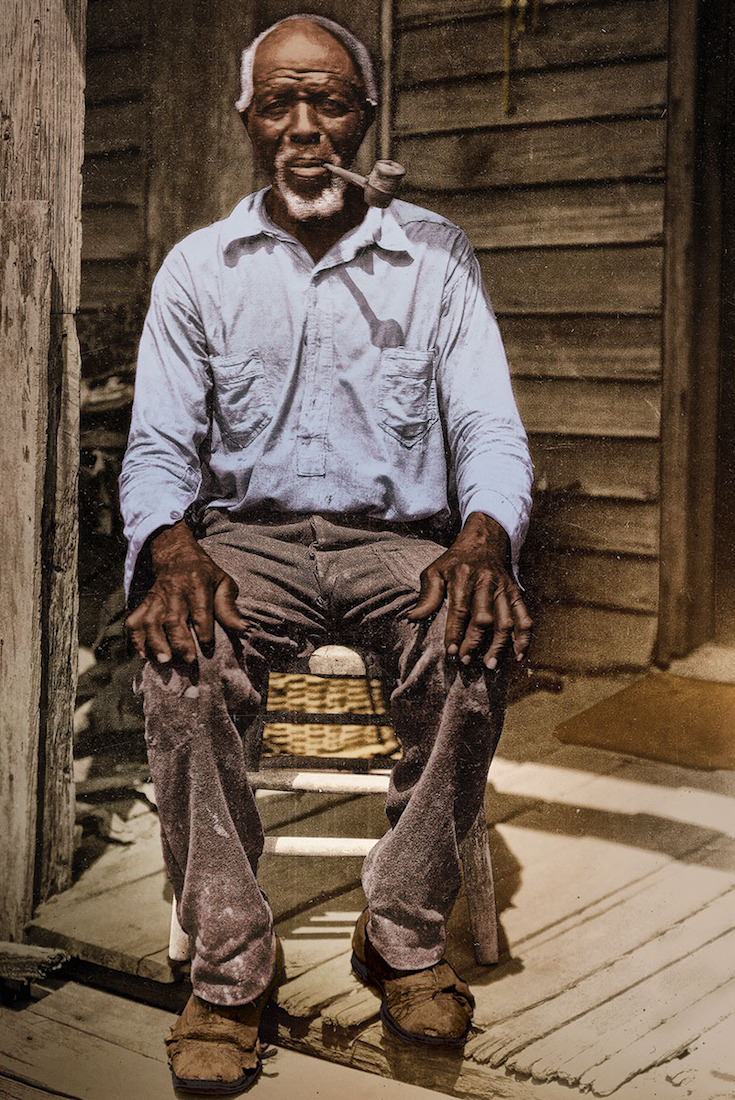

Erik Overbey Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama. Colorization by Gluekit., Featured Image

[dropcap]Their[/dropcap] Eyes Were Watching God is required reading in high schools and colleges and cited as a formative influence by Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou. It’s been canonized by Harold Bloom — even credited for inspiring the tableau in Lemonade where Beyoncé and a clutch of other women regally occupy a wooden porch — but Zora Neale Hurston’s classic novel was eviscerated by critics when it was published in 1937. The hater-in-chief was no less than Richard Wright, who recoiled as much at the book’s depiction of lush female sexuality and (supposedly) apolitical themes as its use of black dialect, “the minstrel technique that makes the ‘white folks’ laugh.” [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

Six years earlier, Hurston had tried to publish another book in dialect, this one a work of nonfiction called Barracoon. Before she turned to writing novels, she’d trained as a cultural anthropologist at Barnard under the famed father of the field, Franz Boas. He sent his student back south to interview people of African descent. (Hurston was raised in Eatonville, Florida, which wasn’t the “black backside” of a white town, she once observed, but a place wholly inhabited and run by black people — her father was a three-term mayor.) She proved adept at the task, but, as she noted in her collection of folklore, Mules and Men, the job wasn’t always straightforward: “The best source is where there are the least outside influences and these people, usually underprivileged, are the shyest. They are most reluctant at times to reveal that which the soul lives by. And the Negro, in spite of his open-faced laughter, his seeming acquiescence, is particularly evasive … The Negro offers a feather-bed resistance, that is, we let the probe enter, but it never comes out.”

[jg-ffw] [/jg-ffw]

[/jg-ffw]

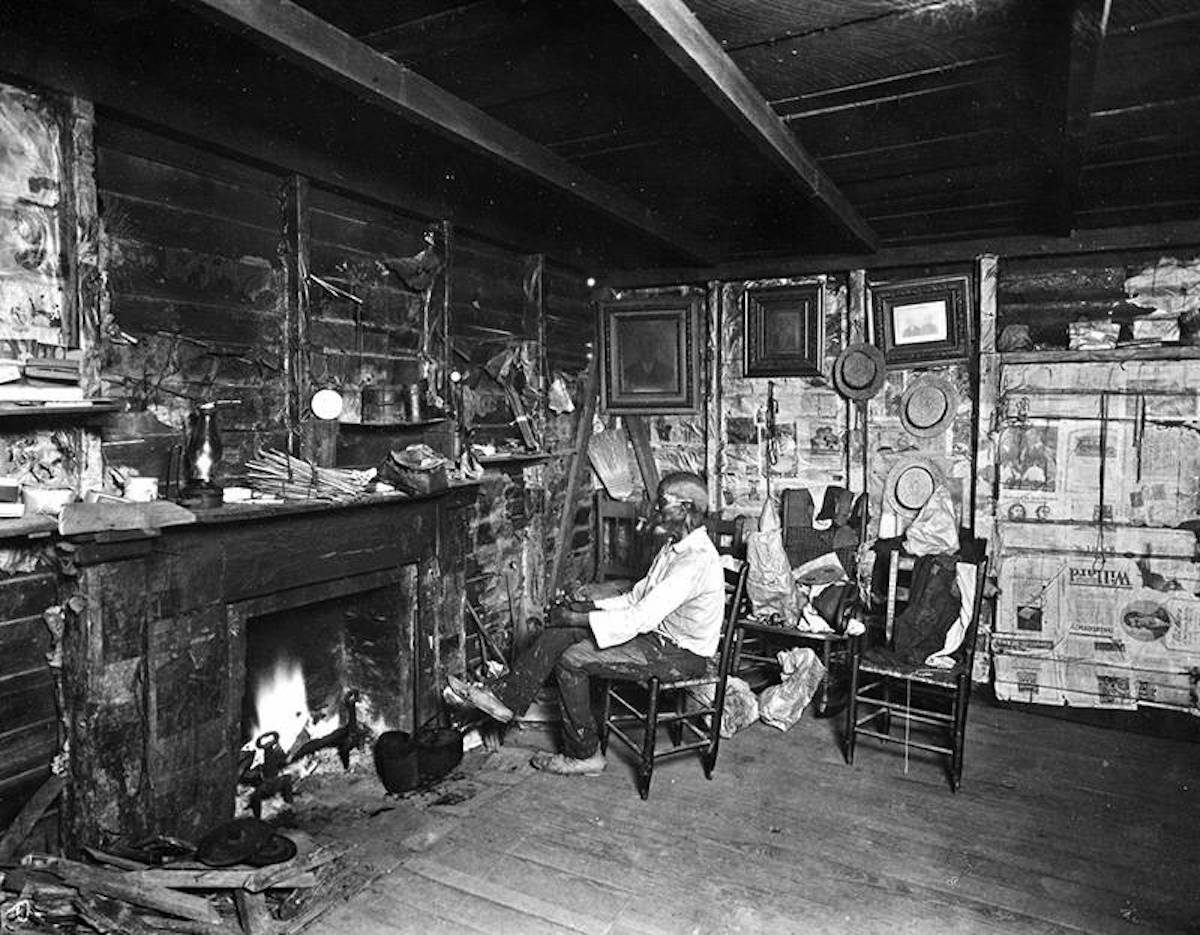

Barracoon is testament to her patient fieldwork. The book is based on three months of periodic interviews with a man named Cudjo Lewis — or Kossula, his original name — the last survivor of the last slave ship to land on American shores. Plying him with peaches and Virginia hams, watermelon and Bee Brand insect powder, Hurston drew out his story. Kossula had been captured at age 19 in an area now known as the country Benin by warriors from the neighboring Dahomian tribe, then marched to a stockade, or barracoon, on the West African coast. There, he and some 120 others were purchased and herded onto the Clotilda, captained by William Foster and commissioned by three Alabama brothers to make the 1860 voyage.

After surviving the Middle Passage, the captives were smuggled into Mobile under cover of darkness. By this time, the international slave trade had been illegal in the United States for 50 years, and the venture was rumored to have been inspired when one of the brothers, Timothy Meaher, bet he could pull it off without being “hanged.” (Indeed, no one was ever punished.) Cudjo worked as a slave on the docks of the Alabama River before being freed in 1865 and living for another 70 years: through Reconstruction, the resurgent oppression of Jim Crow rule, the beginning of the Depression.

[jg-ffw] [/jg-ffw]

[/jg-ffw]

When Hurston tried to get Barracoon published in 1931, she couldn’t find a taker. There was concern among “black intellectuals and political leaders” that the book laid uncomfortably bare Africans’ involvement in the slave trade, according to novelist Alice Walker’s foreword to the book, which is finally being published in May. Walker is responsible for reintroducing the world to a forgotten Zora Neale Hurston, who’d died penniless and alone in 1960, in a 1975 Ms. magazine essay. As Walker writes, “Who would want to know, via a blow-by-blow account, how African chiefs deliberately set out to capture Africans from neighboring tribes, to provoke wars of conquest in order to capture for the slave trade. This is, make no mistake, a harrowing read.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.