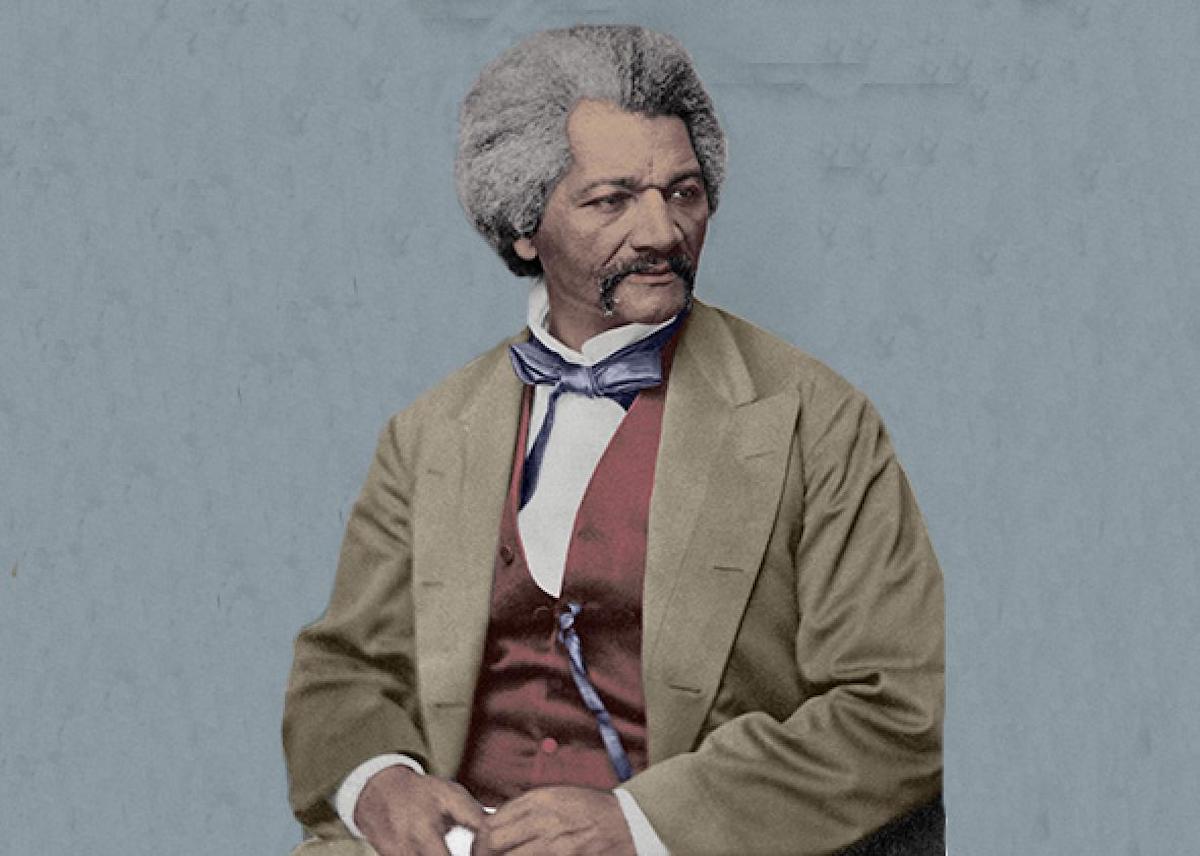

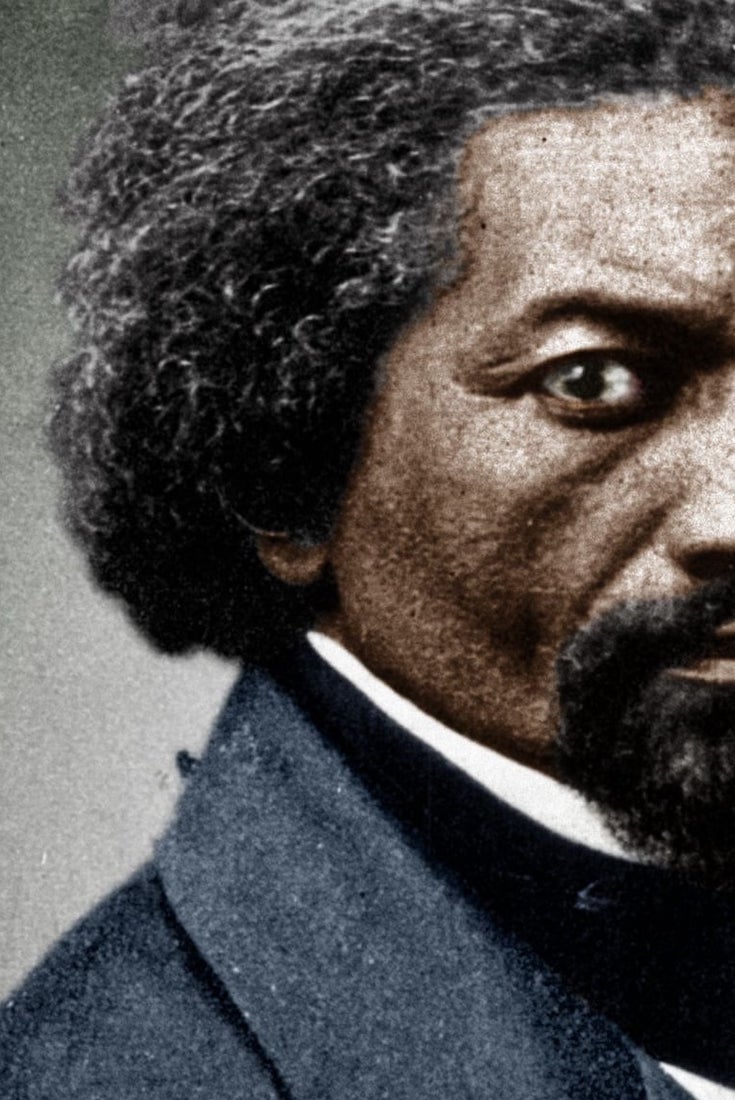

Frederick Douglass, c1866. Photograph: Granger/REX/Shutterstock. Featured Image

[dropcap]If[/dropcap] Frederick Douglass had been born white in 19th-century America, he would be remembered as a self-made man in the style of Thomas Edison. In 20th-century America, postwar, he could have been a counselor to presidents, like James A Baker, or perhaps a media personality, even Walter Cronkite. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

But he was born a slave, in Maryland in 1818, and he escaped to freedom and a life of voice and pen, thundering against slavery and for justice and the rights of African Americans and women – while becoming all those other things as well.

His second wife, Helen, wrote of “the shining angel of truth by whose side I believe he was born, and by his side he unflinchingly walked through his life”. Indeed, Douglass seemed protected. He was taught to read (then a crime) by a white woman, Sophia Auld, in the family that enslaved him. He worked in Baltimore, was converted as a teenager to a strong personal faith, and taught himself oratory from sermons and books. In 1838 he escaped north, making a new life and taking a new surname, adapted from Sir Walter Scott.

As David Blight writes, “Douglass’ great gift … is that he found ways to convert the scars Covey [a slave master] left on his body into words that might change the world. His travail under Covey’s yoke became Douglass’ crucifixion and resurrection.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.