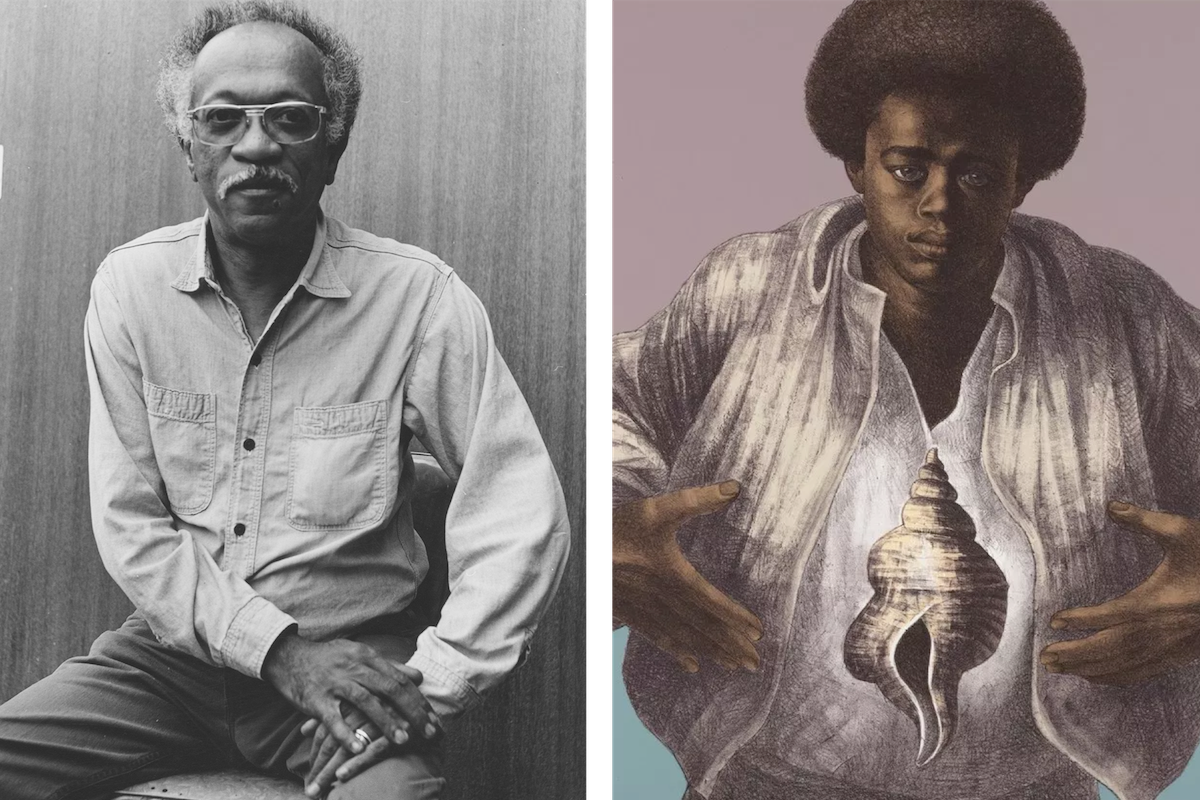

[dropcap]Not[/dropcap] a lot of black people know who Charles White is—which is equal parts heartbreaking and confusing, because it’s hard to overstate his importance as a black artist. White was one of the most successful and influential creatives to come out of the New Negro Movement. His striking, powerful renderings of seminal black figures (including Frederick Douglass, Mahalia Jackson, and Harry Belafonte) were featured on federally funded murals, national calendars, and even Hollywood film sets. He taught Kerry James Marshall. And yet, soon after his premature death in 1979, the art world (and, as a consequence, the black consciousness) largely forgot about him. But isn’t that often the case with black artists? [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

Charles White. The Trenton Six, 1949. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX. © The Charles White Archives Inc. Image Credit.

Charles White. The Trenton Six, 1949. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX. © The Charles White Archives Inc. Image Credit. Charles White. Harvest Talk, 1953. Restricted gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert S. Hartman. © The Charles White Archives Inc. Image Credit.

Charles White. Harvest Talk, 1953. Restricted gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert S. Hartman. © The Charles White Archives Inc. Image Credit.The Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) new retrospective on White—the first major museum exhibition dedicated to him in over 30 years—feels like a necessary revisionist history lesson, an attempt to undo erasure of the artist’s legacy. Walking through the exhibition, it’s astonishing how White’s drawings still deftly capture the black experience. He made figurative drawing a centerpiece of his craft, part of a personal mission to insert black bodies into the westernized canon of art. White put our innate beauty front and center, painting us in a divine, blemish-free light. At the time, the effort was novel and under-explored. Today, it’s on the tip of everyone’s tongue. Black bodies, and representation of them, have become the chief preoccupation of artists like Kehinde Wiley, Toyin Ojih Odutola, and Deana Lawson. The problems of yesterday are the problems of today.

You must be logged in to post a comment.