[dropcap]Let[/dropcap] me begin on a personal note. Over half a century ago, my uncle, the historian Philip S. Foner, rescued Frederick Douglass from undeserved obscurity. Beginning in 1950, he edited four volumes of Douglass’s magnificent speeches and writings, each with a long biographical introduction that chronicled his rise to international renown as a crusader for abolition and racial equality. It is difficult to believe, given his prominence during his lifetime, but Douglass was virtually unknown outside the black community at the time. Almost all of the books about him were by black writers—Benjamin Quarles, Shirley Graham Du Bois, even Booker T. Washington—or by white ones, such as my uncle, oriented to the Old Left and attuned to the problem of racial justice. My own high-school history textbook, by Columbia University professor David S. Muzzey, contained no reference to Douglass (indeed, the only black person mentioned by name in the entire book was Toussaint L’Ouverture). [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

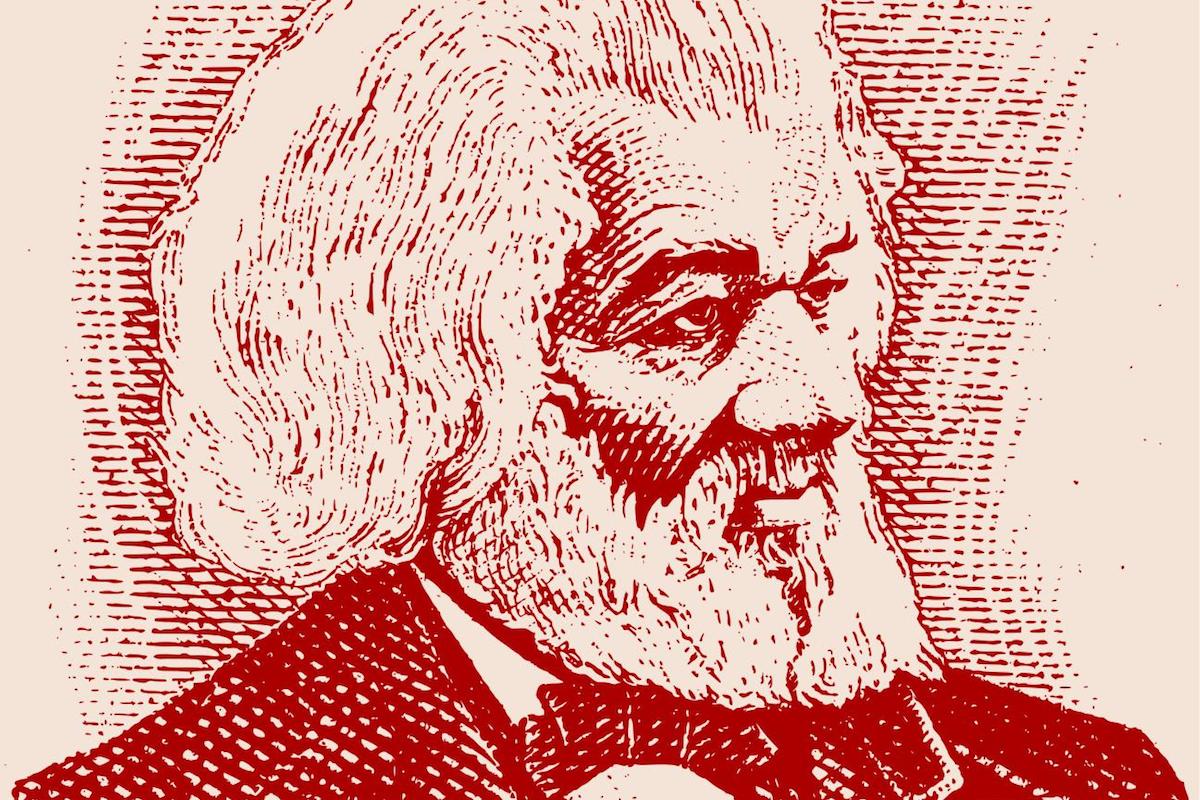

Today, Douglass is ubiquitous. Avenues, plazas, and schools are named in his honor. He has been the subject of poems, novels, and plays and is among the few African Americans whose statues grace the public landscape. Every aspect of his life, it seems, commands scholarly attention. In the past few years, books have appeared about Douglass’s ideas on race and politics; the public reception of his writings; his relationships with women; the similarities and differences between him and his contemporary, Abraham Lincoln; and his ideas on freedom as compared with those of Frantz Fanon and Michel Foucault. There is even a Douglass encyclopedia. Indeed, Douglass’s fame has attained such heights that even President Trump—not known for his deep familiarity with American history—appears to have heard of him.

Douglass’s current status as a national hero poses a challenge for the biographer, making it difficult to view him dispassionately. Moreover, those who seek to tell his story must compete with their subject’s own version of it. Douglass published three autobiographies, among the greatest works of this genre in American literature. They present not only a powerful indictment of slavery, but also a tale of extraordinary individual achievement (it is no accident that Douglass’s most frequently delivered lecture was titled “Self-Made Men”). Like all autobiographies, however, Douglass’s were simultaneously historical narratives and works of the imagination. As David Blight notes in his new book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, some passages in them—especially those relating to Douglass’s childhood—are “almost pure invention,” which means the biographer must resist the temptation to take these books entirely at face value.