[dropcap]Eight[/dropcap] seconds were all Myrtis Dightman needed to make history. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

It was 1967, the first weekend in April, and the lean 31-year-old cowboy lowered himself onto the back of a 1,700-pound bull. He was at a rodeo in Edmonton, in the Canadian province of Alberta, the farthest he’d ever been from his East Texas hometown of Crockett. The air was thick with the stench of livestock and cigarette smoke as five thousand onlookers packed the concrete grandstands.

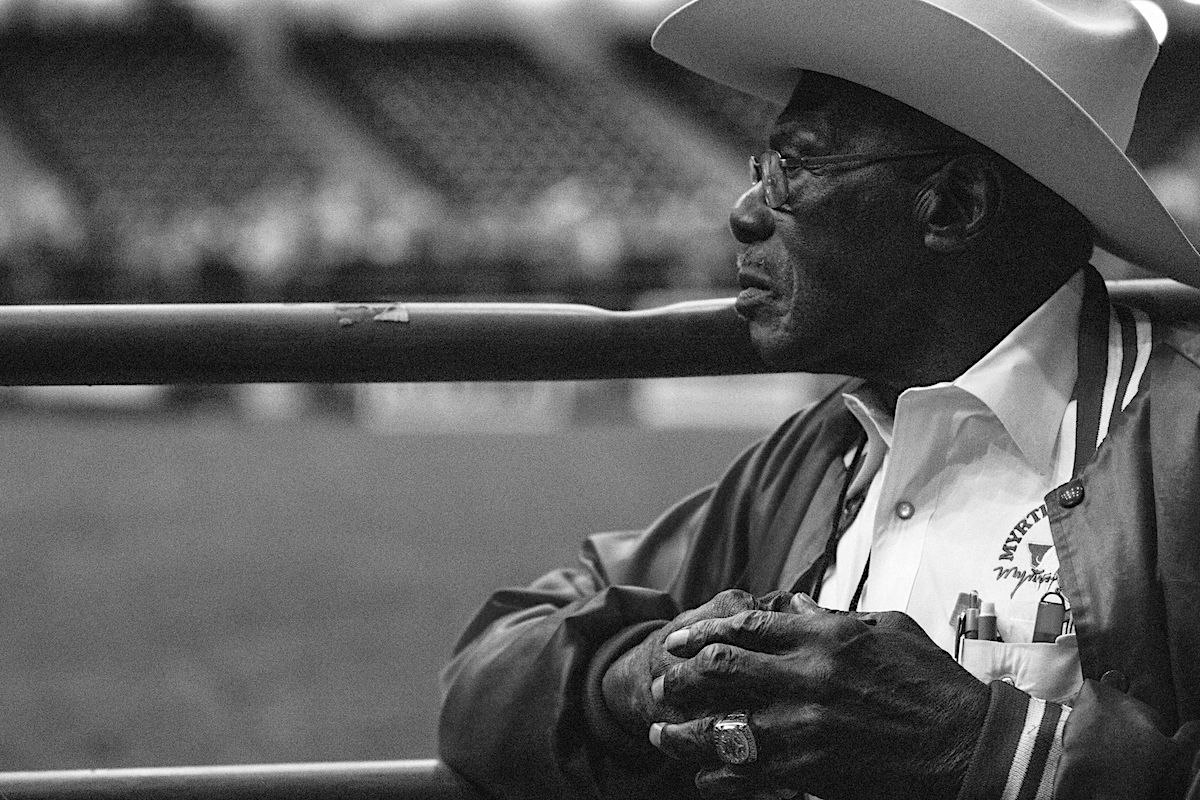

Dightman, dressed in a starched collared shirt and tan chaps with three dark leather diamonds running down the sides, slid his legs around the flesh-and-blood powder keg, careful to keep his spurs turned out. He slipped his right hand into the braided hold behind the Brahman’s muscular hump. Red dust billowed from the bull’s hide as the grass rope—the only thing Dightman was allowed to hold on to—was pulled tight as a hangman’s halter around the animal’s midsection. His hand now strapped in the rigging, Dightman leaned forward until he was nearly looking down between the bull’s horns. He closed his left hand into a fist as he raised it high above his cream-colored cowboy hat.

To make a qualified ride, a cowboy has to hang on for eight seconds without his free hand touching himself or the bull. If he “makes eight,” judges will give the ride a score, with a total of a hundred possible points—fifty for how hard the bull bucked and fifty for the rider’s ability to stay in control. If Dightman held on, this ride could send him to the top of the standings. He took a breath, then nodded. The chute flung open.