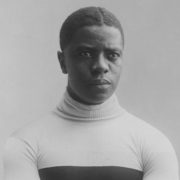

On the afternoon of June 17, 1898, thousands of spectators filled an arena to watch a contest between two men, billed as “Black Vs. White.” The black man was Marshall “Major” Taylor. In the previous 18 months, he had become the nation’s most famous and successful African-American athlete. He was a champion cyclist, specializing in sprints around oval tracks, in velodromes specially built for what was then the nation’s most popular sport. He almost always competed against white racers, and promoters played up the racial angle. This was a decade before Jack Johnson became world heavyweight champion, and a half-century before Jackie Robinson broke the color line in Major League Baseball. It would be Taylor who paved the way.

On this day, at the recently constructed state-of-the-art Charles River Park, a 20-acre facility in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 10,000 people filled the covered grandstands to see if Taylor could beat a famed white rider named Eddie McDuffee. The purse was $1,500, an extraordinary sum that vastly exceeded the annual earnings of most people at the time. Taylor was in the midst of his effort to win the national championship, which was determined by points collected during the season. Given a fair race, Taylor believed he could easily be declared the nation’s top rider. But many white riders sought to keep him off the tracks, invoking Jim Crow rules and, if that didn’t work, death threats. Taylor was not merely seeking to be a sports champion. With every victory, he believed, he could disprove the racist theories that were invoked to try to defeat many blacks before they got a chance to compete at every station of life in the United States.

The Cambridge venue seemed as favorable a venue as Taylor could find. He was a resident of nearby Worcester, and officials across the state had worked to assure that he could compete there unhindered. But even here, the tone turned ugly. A band struck up a popular tune — “The Warmest Baby in the Bunch” — which included lyrics such as, “You’ll all be dazzled when see dis member; you’ll think that you’ve been drinking n—– punch.” Then the band serenaded Taylor’s competitors with the song “All Coons Look Alike to Me,” a ragtime ditty by a black minstrel composer, Ernest Hogan, who profited from the million-selling score but came to regret it. The cover image of the sheet music showed seven stereotyped blacks and the subtitle “A Darkey Misunderstanding.” Taylor had no choice but to stand with his bike during the performance.

By Michael Kranish, The Undefeated

Featured Image, Collection Jules Beau.

Photographie/ Jules Beau

Full Article @ The Undefeated

You must be logged in to post a comment.