By Art Edwards, LA Review of Books

I USED TO THINK novels contained immensities, which came from reading the great works during my college years and the resulting expansion of my mind. I assumed the novels themselves contained huge portions of the world. It took decades for me to understand that novels did not contain the world but were rather distillations of a few struggles of one or more characters, and through these struggles we feel the swelling of our empathetic capacities. It’s a kind of magic, but the trick, at root, is a simple one, in which the reader plays a prominent role.

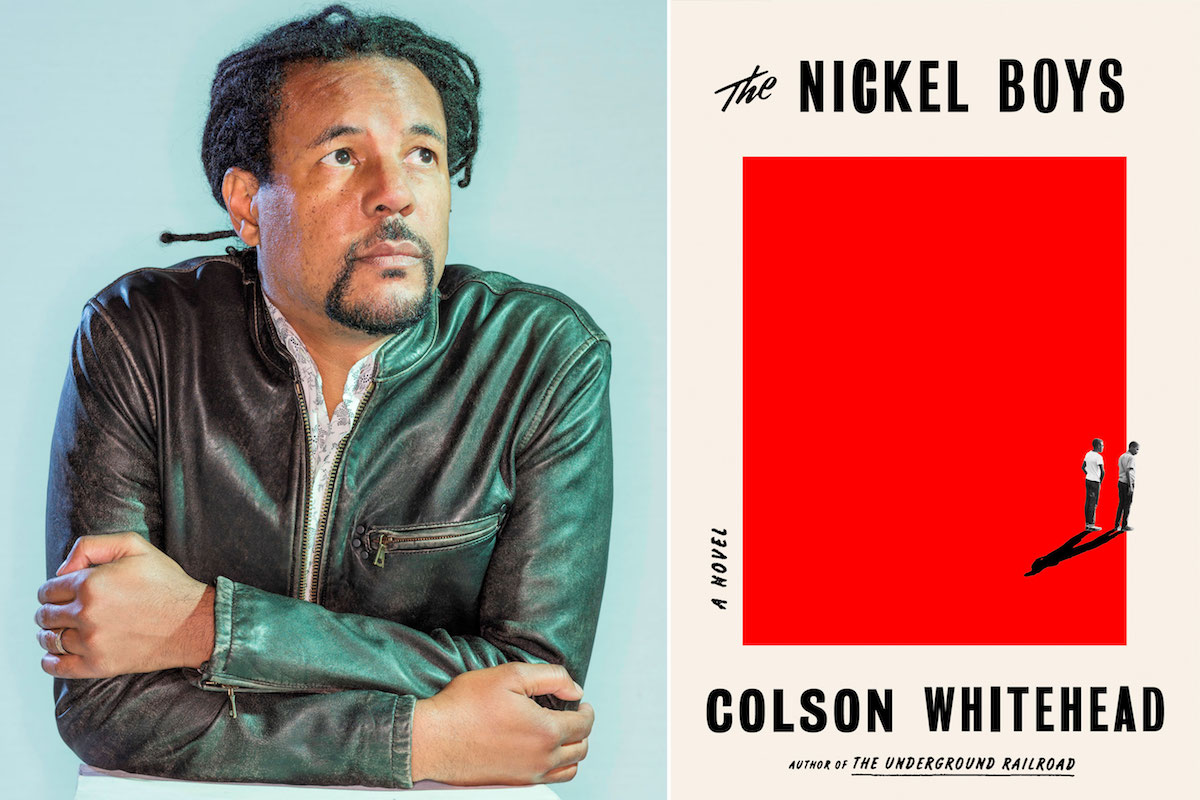

One of our best contemporary magicians is Colson Whitehead, whose latest novel, The Nickel Boys, conjures the lives of students who are subjected to the Nickel Academy, a kind of reform school for boys in Florida circa 1955. The segregated Nickel is actually a corrupt den where kids receive savage beatings for minor or nonexistent infractions, authority figures like to watch boys shower, and the staff sells the supplies meant for the African-American students to the highest bidder in town. Spirit breaking is the rule of the day. Whitehead’s protagonist, Elwood, whose book smarts and love for the lofty rhetoric of Martin Luther King Jr. might make him an unlikely Nickel student, manages to get arrested for someone else’s crime. It’s the kind of situation any African-American boy in the South of any era can’t afford to get caught in. It doesn’t matter that Elwood is morally pristine, resourceful, and a hard worker at his local five-and-dime. “Optimism made Elwood as malleable as the cheap taffy below the register.” At minimum, Nickel challenges each student’s credulity, and compared to some of the other possible fates associated with the school, a good credulity challenge would be getting off easily.

Featured Image, Chris Close, Doubleday

Full article @ LA Reviews of Books

You must be logged in to post a comment.