Lawrence Beitler was sitting on the front porch of his home in Marion, Indiana, when someone asked him to tote his 8×10 view camera to the town square. It was past midnight on August 7, 1930, and Beitler, 44, was a professional photographer who mostly shot portraits of weddings, schoolchildren, and church groups. That night, he would be photographing a lynching. He “didn’t even want to do it,” according to a later interview with his daughter, “but taking pictures was his business.” [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

By the time Beitler arrived on the square, a jubilant mob of nearly 15,000 white men, women, and children had gathered. Earlier that night, a group of vigilantes had charged the county jail to seize two black teenagers — Thomas Shipp, 18, and Abram Smith, 19 — who’d allegedly raped a young white woman and murdered her boyfriend. Beitler took one photo of Shipp’s and Smith’s brutalized bodies hanging from a tree, the crowd of eager onlookers before them, and left.

Lynching, in the American imagination, is considered to be solely the provenance of Confederate racism, one of the most prominent examples being the 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi. Yet the most notorious lynching imagery prior to Till came from Union towns: Duluth, Minnesota; Cairo, Illinois; Omaha, Nebraska — and Marion, Indiana. It is Beitler’s photograph, in particular, that has served as the most glaring visual reminder of the country’s decades-long spectacle of racism and public murder. The photo of the lynching of two Indiana teenagers would never grace the pages of the local paper. But the image is everywhere.

It was Beitler’s photograph that inspired Abel Meeropol to write his anti-lynching poem “Strange Fruit” in 1936, which Billie Holiday would later record and make famous. Just last month, a decade-old mural adaptation of the photograph in Elgin, Illinois, which features only the faces of the white participants, came under public scrutiny as people discovered the image’s origin.

I can’t say exactly when I first encountered the image. It might have been as an undergrad at Columbia, in the library of the black students’ lounge as I thumbed through a copy of Ralph Ginzburg’s 100 Years of Lynchings. But my understanding of its significance came in the late summer of 1996, when a friend and I visited America’s Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM) in my hometown of Milwaukee.

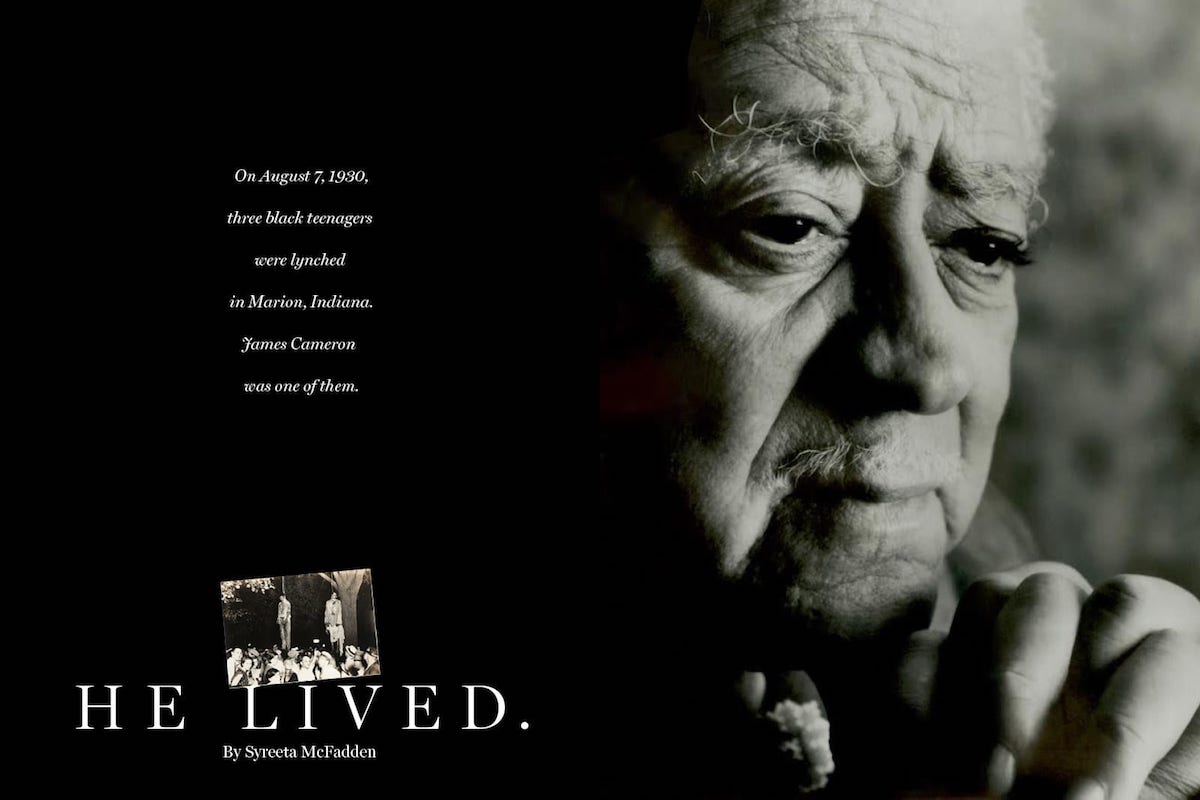

When we entered the main exhibition room, there was a built-to-scale rendering of Beitler’s photo made out of wax, including the facsimiles of Shipp and Smith hanging from the tree. “Did you know that there was a third boy they tried to lynch that night?” our museum guide, a tall but frail older man, asked us, his voice warm and gravelly. We didn’t. Our guide went on to explain that there were actually three ropes strung up on the maple tree in Marion on August 7, 1930. A third teenager had been dragged from his jail cell to the courthouse square. His name was James Cameron and he was the only known person to have ever survived a lynching in America.

You must be logged in to post a comment.