[dropcap]H[/dropcap]aywood “Red Dog” Fennell was finishing up work for the day, headed back to his cell at Pennsylvania’s largest-capacity prison, when a friend called him over, eager to share the news that had lit up the men’s tiny TV screens and sent shouts and whistles echoing down the long, cavernous cell block. It was June 25, 2012, and the U.S. Supreme Court had just ruled that mandatory life sentences without the possibility of parole were unconstitutional for juveniles. Pennsylvania had imposed that sentence on more kids than any other state—some 500 of them, many now in their 40s, 50s, and 60s. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

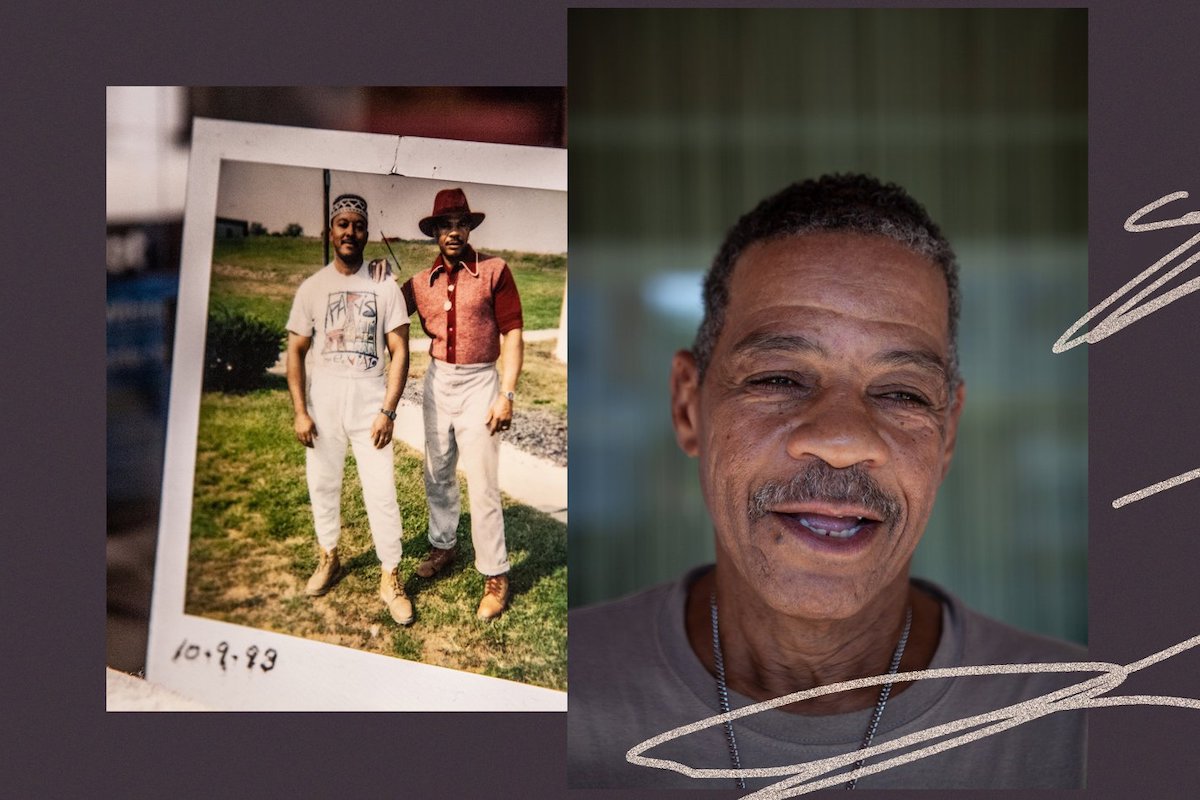

Men who still had their mothers called home to share the news. The jailhouse lawyers got creative with petitions to speed their release. The religious men said prayers. Fennell didn’t see much cause to celebrate. Forty-eight years of incarceration for a role in a fatal mugging when he was 17, and 11 denied commutation applications, had hardened him against fantasies of freedom. Besides, Fennell was 20 years old by the time he was convicted and sentenced. He figured the Supreme Court decision didn’t even apply to him.

But then lawyers started coming from the Philadelphia public defender’s office, driving up the country road to Graterford state prison, set in what had once been rolling farm country and turned into suburban sprawl during Fennell’s time inside. Pennsylvania was resisting the ruling, declaring that it wasn’t retroactive, but the lawyers said it was only a matter of time before a court would disagree. Indeed, in 2016, a follow-up Supreme Court decision made it clear: The 2012 decision must be applied retroactively to the more than 2,000 people like Fennell who had been serving mandatory life sentences without parole for crimes committed when they were juveniles.

You must be logged in to post a comment.