By Monica Drake, The New York Times

Almost as soon as you settle in to watch the 1939 melodrama “Lying Lips,” you can figure out who is the victim, who is the villain and who is the hero. And even if you know how it all will end, you want to watch anyway.

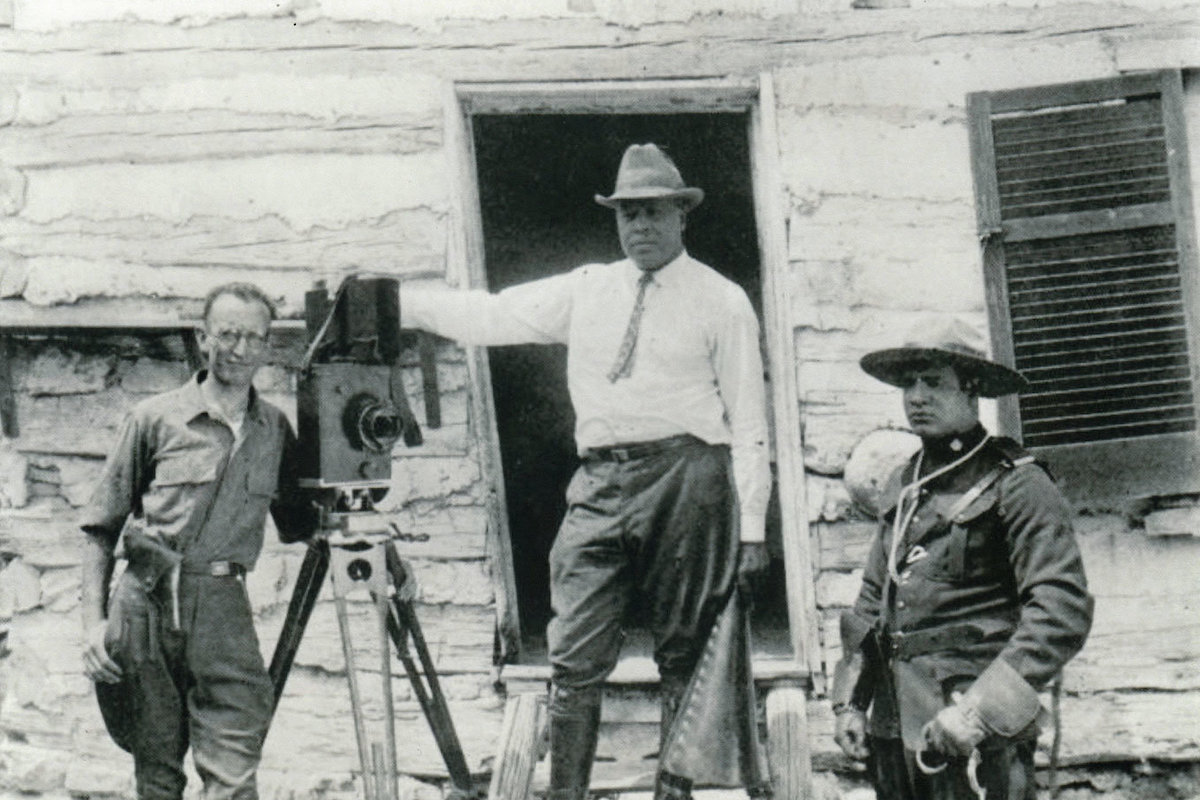

That was the beauty of the filmmaker Oscar Micheaux. He made you want to soak up the exuberance he clearly felt in delivering a whole new way of telling stories.

The 40 or so films that Micheaux wrote, directed and produced from 1919 to 1948 carry with them the added excitement of black characters doing things that at the time seemed unthinkable onscreen. Women could be damsels in distress, intelligent enough to plot and scheme, and were able to recreate the feel of a black-and-tan show on black-and-white film. Men were rugged and sometimes flawed but rarely surrendered their masculinity for comedic effect.

The performances were rollicking good, and they concealed the fact that Micheaux was essentially an outsider artist as filmmaker, prefiguring today’s independent black producer-directors like Spike Lee and Tyler Perry. He was a gifted visionary, with an eye for talent, evinced by decisions like casting the dazzling stage actor Paul Robeson in his first role on the big screen. His films depicted the basic humanity of black characters wrestling with issues like racial ambiguity, while at the same time countering the racist tropes in works like D. W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” (1915).

Full article @ The New York Times

Featured Image, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.