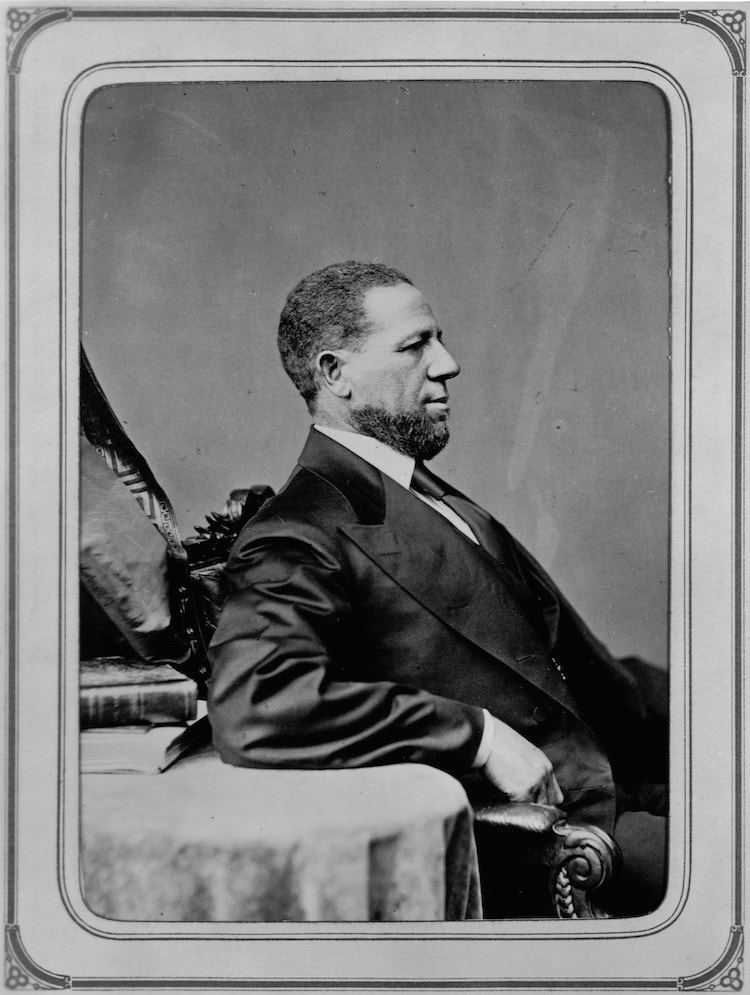

Elected 150 years ago, Hiram Revels was the first.

A few days ago, 300 people gathered in the Old State Capitol in Jackson, Miss., to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the election of Hiram Revels as the nation’s first African-American member of Congress.

As nearly everyone knows, in the nation’s more than two centuries of existence Barack Obama is our only black president. Less familiar is the fact that of the nearly 2,000 men and women who have served in the Senate only 10 have been black. Of these, Revels and Blanche K. Bruce were elected from Mississippi during Reconstruction. These numbers offer a stark reminder of the almost insurmountable barriers that have kept African-Americans from the highest offices in government and of how remarkable a moment Reconstruction was in the history of American democracy.

Before the Civil War only a handful of black officials existed anywhere in the country — just a few justices of the peace in Northern abolitionist communities. But during Reconstruction some 2,000 African-Americans occupied positions ranging from members of Congress to state legislators, sheriffs, city councilmen and others. This unprecedented experiment in biracial democracy aroused intense opposition from adherents of white supremacy, at that time concentrated in the Democratic Party, who sought to undermine Reconstruction through outright violence and a campaign of vilification that portrayed black officials as ignorant, corrupt and unfit for public service. The New York World, the nation’s leading Democratic newspaper, described Revels as “a lineal descendant of an orangutan.”

Featured Image, Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels.

Mathew B. Brady/Library of Congress, via Getty Images

Full article @ The New York Times