Evelynn Hammonds, who chairs Harvard’s department of the history of science, has spent her career studying the intersection of race and disease. She wrote a history of New York City’s attempt, a century ago, to control diphtheria, and is currently at work on a book of essays on the history of race, from Jefferson to genomics. Hammonds’s area of expertise is especially relevant today: while the data is incomplete, at this point in time, African-Americans represent nearly a third of U.S. deaths from the coronavirus pandemic and thirty per cent of covid-19 cases, despite making up only about thirteen per cent of the population. Hammonds noted recently, “This new development of what has happened with the pandemic with respect to African-American communities” is “perhaps an old development.”

I spoke by phone with Hammonds, who is currently hosting a series of Webinars with academics and experts at Harvard on African-Americans and epidemics in American history, from the eighteenth century to the present day. As she stated in one of the sessions, “I can’t imagine saying that we have to wait until this pandemic has passed to make clear what kinds of structural inequalities and implicit and explicit biases are at work.” During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, we discussed why African-Americans were once thought to be immune to various diseases, how this belief morphed into the fear that they were spreaders of contagion, and what lessons can be learned from a Civil War-era smallpox outbreak.

Have you been thinking about the coronavirus in a historical context, and, if so, what specific context?

I think any historian who has worked on the history of disease has been thinking about the coronavirus in historical contexts, and there are many, many resonances that kept appearing in press reports of all kinds. About four weeks ago, I began to be particularly interested in the fact that I wasn’t hearing about the pandemic having an impact on African-American communities. You heard stories that said this disease affects us all, but, knowing what we know about the ways in which epidemic diseases always lay bare and make visible inequalities in a society, I was surprised that I wasn’t hearing very much about what was happening for African-Americans and Latinos, and also very poor people in general. Then the news burst on the scene that, in many of the hardest-hit areas, African-Americans were disproportionately impacted. And at that point I was having a conversation with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and I decided to host a Webinar on the impact of epidemic disease on African-Americans from 1793 to the present.

By Isaac Chotiner, The New Yorker

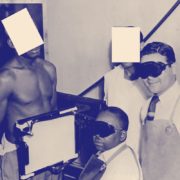

Featured Image, The historian Evelynn Hammonds talks about how false theories of “innate difference and deficit in black bodies” have shaped American responses to disease, from yellow fever to syphilis to COVID-19. Photograph Courtesy CDC / Alamy

Full article @ The New Yorker