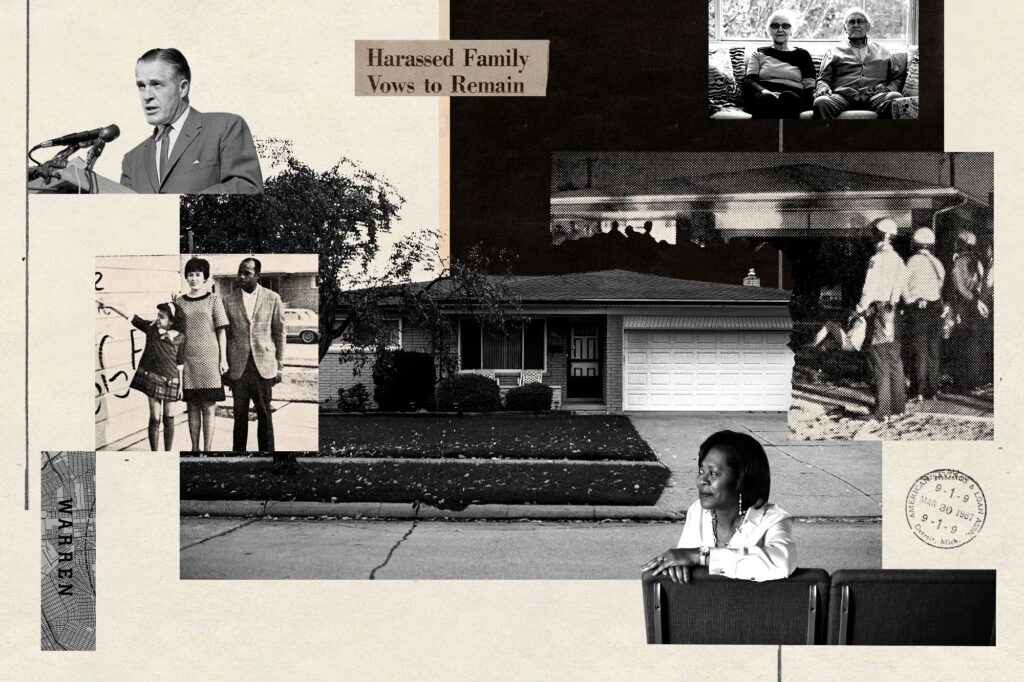

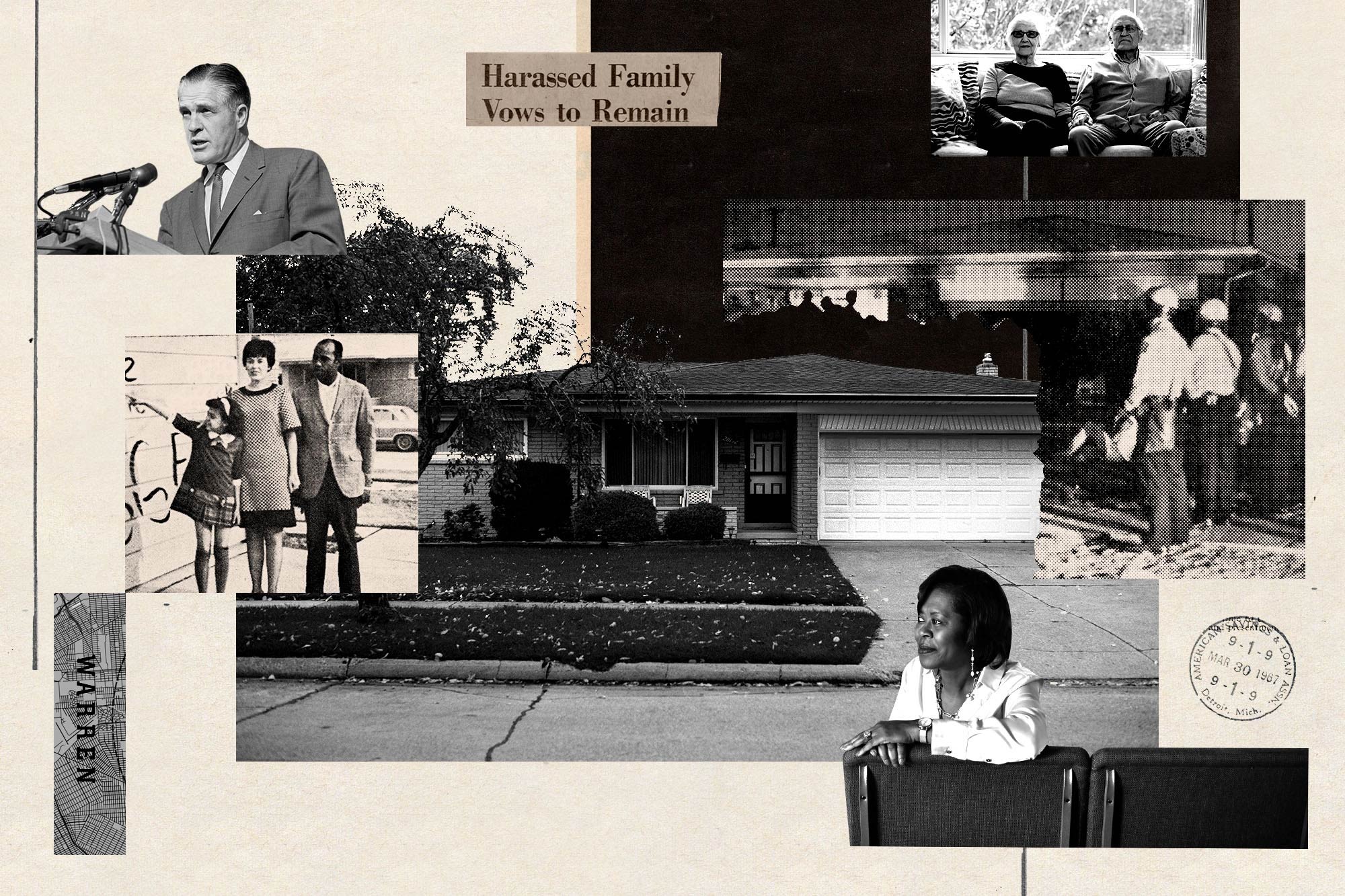

What happened to the Bailey family in the Detroit suburb of Warren became a flashpoint in the national battle over integration.

By Zack Stanton, Politico

Illustrations by Mark Harris for POLITICO; Photos by Brittany Greeson for POLITICO

The Battle for Buster Drive

WARREN, Michigan — On the night of June 13, 1967, Mary Killeen woke from a fitful sleep to see a tank rumbling down her street.

A phalanx of a dozen or so police in riot gear marched alongside and they were headed right toward her. Directly across the street, a seething crowd of 200 to 300 white people were swarming the house of her newest neighbors. It had been building for days. The crowd trampled the fresh sod. They screamed and shouted at the occupants inside, their faces lit by car headlights and the flicker of gas lamps on front lawns. They surrounded the home, staring in. Some threw rocks at the windows. Some pounded on the outer walls, like a shark bumping against the underside of a life raft.

The home belonged to the Baileys. Carado, his wife, Ruby, and young daughter, Pam, had moved in on June 5, a week before. There were new people moving in all the time to the Wishing Well subdivision — Mary Killeen, with her husband and two daughters, had only just got there herself. But the Baileys were different from their neighbors in at least one way: Carado was Black and Ruby was white.

Neighbors didn’t initially know this. Carado worked the night shift at General Motors’ Fisher Body plant, often leaving and returning home under cover of darkness. No one had seen him. Curious neighbors watered their lawns late into the evening, a pretense to be outside and possibly catch a glimpse of the mysterious new family. Once they did, rumors had started spreading fast, shared in hushed tones over backyard fences and front-porch visits.

“‘They shouldn’t be here.’ ‘We’re a good neighborhood and we don’t want Blacks in this neighborhood.’ That kind of talk,” Killeen says of the reaction on Buster Drive. “It just took a few days, and then it really escalated very quickly.”

On their fifth night in the neighborhood, the Baileys’ telephone lines were cut.

On the sixth night, the police did nothing. They just watched as neighbors — 80 to 100 of them — threw smoke bombs and broke windows at the house that looked exactly like their own. Gov. George Romney threatened to call the Michigan state police.

On the ninth night, embarrassed into action, members of the Warren police department put on their riot helmets and marched behind a rumbling tank to rescue the beleaguered family at 26132 Buster Dr.

It was that kind of summer in America. Big forces were feeding the unrest. Bipartisan civil rights legislation was advancing in Washington, and protests for racial equality — often centering on jobs and housing — were seemingly everywhere. Violent encounters between police and Black people became flashpoints that quickly overwhelmed the non-violence ethos of the Civil Rights Movement. In the span of two weeks (from June 2 to June 17), riots broke out in a half-dozen major American cities (Boston, Tampa, Cincinnati and Atlanta among them), leading to numerous deaths and hundreds of millions of dollars of damage. The battle that was taking place on Buster Drive in Warren was but a small sideshow to the images playing on the nightly news and would soon be eclipsed by the devastating violence that would erupt a few miles away in Detroit in July. But what would transpire over the coming days and months and years on Buster Drive would actually have profound consequences for race relations in America and shape the national political landscape in ways that are still being felt today.

A telegenic housing secretary with presidential ambitions would use the Baileys’ plight to launch a bold plan to desgregate all of America’s suburbs.

Local officials in Warren, stoked by the rage of their white constituents, would stymie his efforts, even though it meant forfeiting millions of dollars of federal aid.

A Republican president facing reelection would torpedo his secretary’s plan, empowering the white middle-class voters he considered crucial to his victory.

Those voters, in turn, would make this corner of suburban Detroit the unofficial capital of America’s white middle class, and shape the strategy of presidential hopefuls of both parties for decades to come.

Ultimately, the whites-only fortress of Warren and surrounding Macomb County would crumble, overwhelmed by the consequences of self-defeating choices made decades before. Like suburbs across the country, it would become more diverse — and increasingly Democratic. But it would retain the scars of unhealed racial fault lines first laid down in 1967 — a de facto segregation that would make Macomb County a prime target for populist conservatives bent on appealing to white working-class voters. Few suburbs would suffer the same headline-making unrest or the targeted federal scrutiny as Warren. But its prominent role in the massive demographic and political shifts of the last half century would ensure it remained an important bellwether heading into the 2024 presidential election when, once again, Macomb County would find itself a political battleground for the nation’s all-important suburban vote.

But before any of that could happen, the Baileys had to outlast the mob.

Read full article @ Politico

You must be logged in to post a comment.